“Can you imagine what life must have been like with a four meter high wall and an almost 70 meter wide death strip right at your doorstep?”. This quote is displayed outside a key touristic attraction in Berlin that revolves around commemorating life in the city when the Berlin Wall came up, snaked its way through and dissected it into two incoherent worlds. Michael Jabareen, 29, a Palestinian who lives and works in Berlin as a freelance artist recalled first reading this quote. He grimaced with a look of disgust on his face. “I felt very offended by this quote when I saw it in a public space in the middle of Berlin. My family has been separated by Israel’s occupation and annexation wall for decades. I don’t have to “imagine” what Germany wants me to. We live this everyday back home in occupied Palestine”.

Michael comes from Al Taybeh village – outside of Jenin town north of the occupied West Bank. He grew up under the Israeli occupation’s brutal oppression of Palestinians. He encountered a tank at eight years of age during the infamous raid on Jenin refugee camp in the year 2002. As a youth and young adult he went through Israeli checkpoints. He is unable to visit Jerusalem without an Israeli occupation military permit. Since the Jabareen family has its roots in Umm El Fahem, he watched his extended family get separated by the 712 kilometre long (of which 70 are completed) and eight meter high Israeli occupation wall. As an architect and multidisciplinary artist, Michael used his artistic skills and creativity to engage in socially or politically themed projects to contribute to the expressive resistance movement at home.

Fast forward to November 2022, on a partly cloudy autumn morning in Berlin, I sit with Michael over lunch. We discuss our journeys that brought us together in the city. He first visited in 2019, to take part in a theatre festival. I first visited Berlin in 2012. He decided to return to the city in 2020 to obtain degree in Visual and Experience Design. My decision, in 2022, to spend four months in the city to work on a project documenting stories of Palestinians in the exile. We stop at May 2022: the time when the Berlin local government made a U-turn on its decision to allow the commemoration of the Palestinian Nakba to proceed.

Common knowledge about German history seems to start and stop at World War II and the Holocaust. What followed the Cold War, the occupation of the country and the rise and fall of the Berlin Wall are discussed in silos. Internally, it is apparent that the German society did not adequately deal with its country’s dark history. Few connect the dots between Germany’s colonial history in the African continent and the attempted annihilation of approximately six million Jews with other minorities.

Since the establishment of the Zionist state on stolen Palestinian land in 1948, Germany has taken it upon itself to provide blind political, monetary and military support to Israel as a way to make up for the bottled-up public guilt from the Holocaust. While it does also support the Palestinian Authority, most of German tax payers’ money goes into projects that contribute to the oppressions of the Palestinian people such as “security sector reform” schemes.

In 2017, Germany adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) non-legally binding revised definition of antisemitism that conflates Zionism with Judaism. As such, any criticism to the State of Israel is labeled as “anti-semitism” under this definition. Two years later, the German parliament adopted another non-legally binding motion to combat the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. BDS advocates for Palestinians’ equal rights and freedoms by calling for the boycott of Israeli linked goods, cultural and academic activities. Again the German state drew similarities between the dark days of the Third Reich and its persecution of the Jews – and Palestinian led resistance of the Israeli occupation and reclaiming the right to self-determination. Moreover the country’s immigration policies towards Palestinian refugees are unjust, labelling them as “stateless” or “unknown” by the system [1].

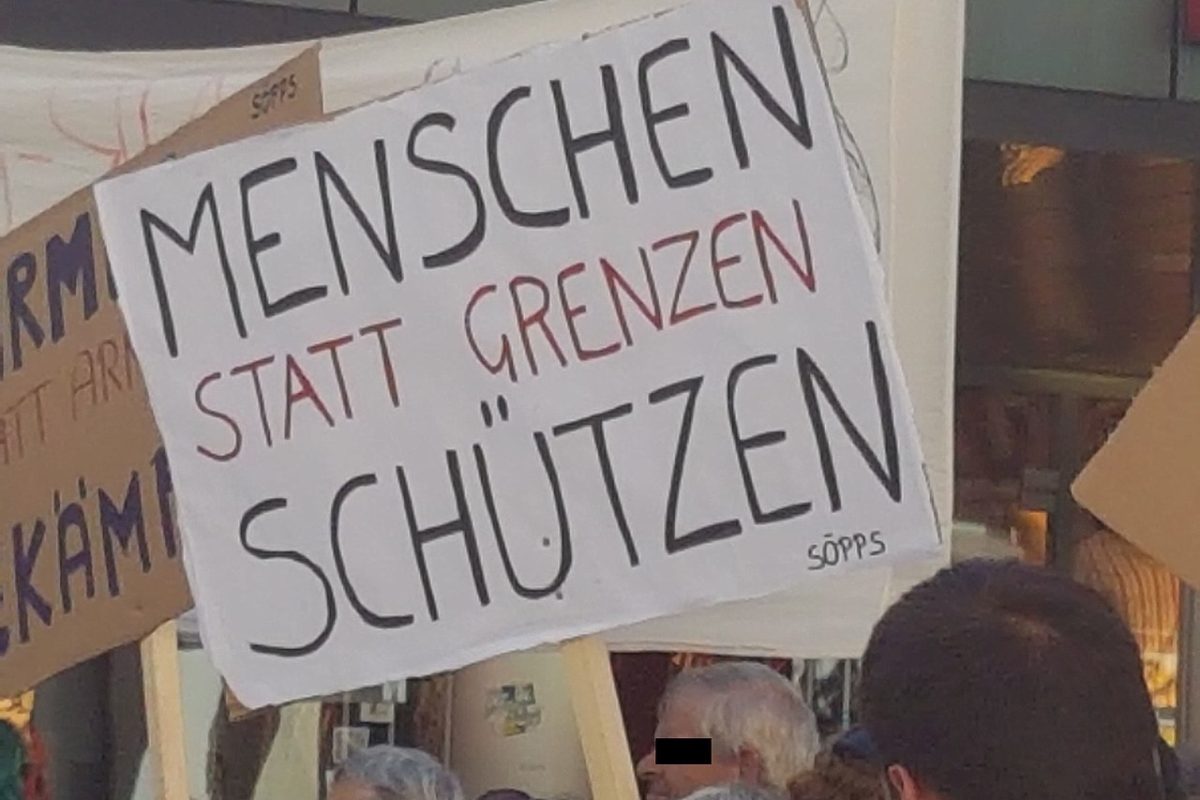

All the recent collective anti-Palestinian moves by the German state culminated in the 2022 Nakba demonstration ban. While the organisers cancelled the demonstration after the imposed rules, people still stood in solidarity. Flags, the Palestinian kufiyyeh and other symbols were raised in silence on May 15th 2022. Responding, German police arrested 170 individuals, 27 being accused of taking part in an illegal gathering, and of carrying the Palestinian flag. At the time of writing seven trials have been held. While two cases involving a German and a Jewish activist were instantly dropped by the court, the others are ongoing, mainly involving Palestinian and other activists from minority groups.

The bottom line is, Germany equates pro-Palestinian symbols and acts of solidarity as anti-semitic. This view of the state, gives it the right to silence pro-Palestinian voices. In a country that prides itself upon the right of freedom of expression and guaranteed cultural freedoms for those who reside on its soil, these recent acts are an audacity. They are a clear form of discriminatory oppression of a one group, whereby both Palestinian and Jewish identities are flattened to simplistic propaganda labels of “islamic terrorists” versus “victims”.

As a Palestinian in the exile, listening to Michael’s and other people’s accounts of the May 2022 events and witnessing what followed brought on a mix of emotions including anger, disgust and resentment. I spent many weeks contemplating those feelings. How can outright right- wing racist parties be allowed to demonstrate in the name of freedom of expression, while Palestinians, who live under a settler colonial regime, and their allies cannot do the same? How dare a state place the burden of its own historical crimes on Palestinians in the exile? Why do Palestinian or pro-Palestinian forms of art come under scrutiny, to the extent of banning them by withdrawing financial support? Why do we have to amend our resistance language to conform with the white-washed narrative around our struggle? So many questions floated in my head during this period, during which I also read and researched through the visual archive of German history for inspiration.

In January, after a short break away from Germany, I decided to use my camera and photography skills to translate my emotions and thoughts into visuals. Through a sequence of staged and abstract images, I wanted to juxtapose key monuments erected around Berlin that mainly commemorate the Holocaust and the Wall. My choices stemmed from my belief that the points in Germany history that led to the Holocaust are closely linked to the ongoing blind support to a settler colony in Palestine. In other words, a context where minorities were viewed as sub-humans at a certain point in time (Jews in this case) is one that still accepts viewing another group of people, i.e. Palestinians, through the same colonial lens. The Holocaust is employed by politicians from all sides of the political spectrum for their own political gains. Even Jews who argue against Germany’s anti-Palestinian actions are labelled as “self-hating”. Indeed, pro-Zionism and anti-semitism are two faces of the same coin.

The Berlin Wall on the other hand is an example of what every similar structure stands for: occupation, colonisation and oppression. Although it is half the size of its Israeli counterpart, its negative impacts on those who lived to experience its time are immense. They are commemorated by Berlin in more than one location around the city. From these, and its construction; dimensions; commemorations of those who resisted it and those who were killed trying to escape from one side of the wall to another – one cannot escape this memory in Berlin. The power of the general public that jointly brought down the wall is also displayed in public spaces. The hope that moment brought on to the world was immense. Therefore, consistent with the German experience, I attempted to commemorate our slain brothers and sisters due to the occupation, our collective and unstoppable tide of pro-Palestinian voices and our hope for freedom.

The fact that only four participants took part in this project reflects the real fear among pro-Palestinian activists, of negative repercussions and false accusations of “anti-semitism”. These in turn could impact their work or immigration status in the country. So I made sure that any in this project were kept anonymous, excepting myself. Because of the limited number of participants, I asked Michael to join me as a collaborator. He added his digital line illustrations to chosen images to enhance their story. Those who took part in this project also contributed with text in Arabic and English to relay their own emotions and thoughts.

The result are black and white images, entitled “Cacti: A Visual Protest Against the Silencing of Palestinian Voices in Germany”. It is a body of work that I will forever be proud of. We joined forces to relay our collective anger, frustration and hopes for a future where we are free to express ourselves, our art and our identities. Cacti have traditionally surrounded Palestinian lands.They remain silent witnesses of depopulated villages and to the continued colonisation of our home. They symbolise beauty, continuation and tough resistance. When one Palestinian voice is raised, it echoes and spreads like cacti. It shall never be silenced. In spite of forces like those in Germany.

You can see a gallery of Rasha’s Cacti photos here.

Footnotes

- Palestinian refugees, especially those from Lebanon, mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, are given an “unidentified” status. This means that they are denied formal refugee status and related right to work and other benefits. At times, this extends to Palestinian holders of Palestinian Authority IDs. This also means that they are not protected from deportation. But that is not possible as Lebanon never signed an agreement with the latter to take them back. As a result, they are “tolerated” by the German government, which means that their deportation is delayed or on hold for the moment. Palestinian-Syrians receive a more stable refugee status.