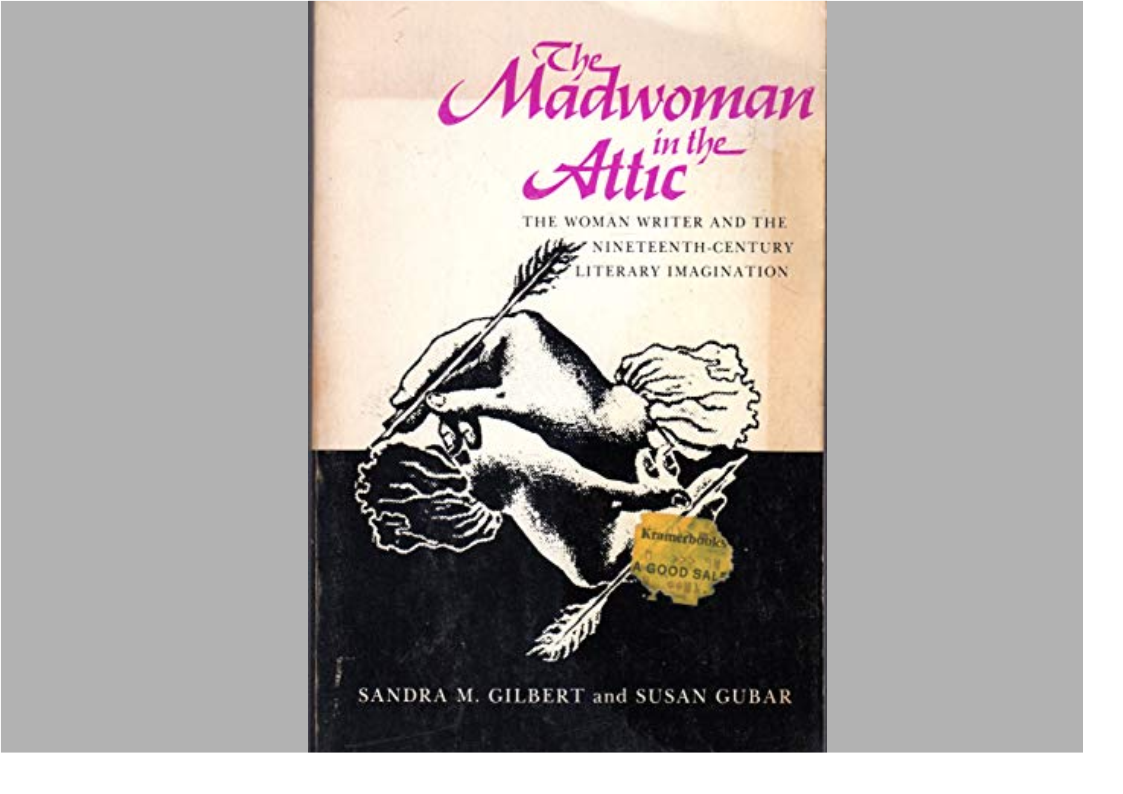

Sandra M Gilbert died last month. Gilbert was best known as the co-author (with Susan Gubar) of the pioneering book The Madwoman in the Attic, which caused literary scholars to rethink how women were portrayed in 19th Century literature. Recovering academic Richard Bradbury looks back at how Gilbert helped reshape how we look at the novel.

When I started to study literature at a British university in 1975 the three core courses were modern(ist) English literature, the European epic and Medieval English literature. During that year not a single set book had been written by a woman. That this is now unimaginable is as a result of years of work – teaching, researching, writing – on the part of students and academics. That work has reshaped the understanding of literature both in universities and – probably more importantly – beyond.

Sandra Gilbert’s work, most often in collaboration with Susan Gubar, played an essential part in that transformation. As I was starting my studies they were beginning work on a book that would, in time, transform many departments of literature. That change took two forms: first, a new contextualisation of nineteenth century ‘classic’ texts and, second, the introduction of other texts as a way of reimagining those ‘classics’.

Let’s look briefly at the way that worked. My first example is their most famous. Jane Eyre. The title of their book – The Madwoman in the Attic – shifted the readers’ attention away from the march of Jane from rebellious child to “Reader, I married him” via a challenging relationship with Rochester. Shifted our attention, as it were, from the marriage failure in the chapel in the grounds of Thornhill to the obscure spaces at the top of the house. Now, Jane’s previously reliable and transparent voice became marked by prejudice as she sees the first Mrs Rochester as a crazed beast. Gilbert and Gubar fix on this moment to reveal the previously smooth surface of the novel as pitted by the acid of history.

Now the first Mrs Rochester becomes a prisoner enraged by her husband’s misogyny and racism whose act of destruction as she burns the house becomes a final gesture of defiance. Now, the designations of misogyny and racism are upended.

This wasn’t, of course it wasn’t, the work of these two writers alone. The male (yes, it needs to be said even now) guardians of literature and history were being questioned, elbowed aside, by a generation of thinkers and writers. Kate Millet, Marilyn French, Elaine Showalter, Jane Marcus, Gillian Beer, and many more besides, were reclaiming the past. And in doing so began to change the present and, more tenuously, the future.

Even more obviously this small work was a part of the much larger, more important, upsurge of second wave feminism that swept through the 1970s and on into the 1980s. From our place in 2024 it is hard to look back past those achievements and the ways in which they changed the landscape of political, intellectual, social discourse; of life. Yet if we don’t do that we will be disempowered in our attempts to forestall the current political, intellectual and social assault on those changes.

Back to that book. This alteration of perspective, this way of reading aslant of the foregrounded rhetoric was also part of the wider development of reading strategies that took into account the existence of the reader as a constructive part of the text’s meanings. That plural is crucial, acknowledging as it does the many existences, the many subject positions, of readers.

There is one element of the commentary of Charlotte Brontë’s novel that I do have to take issue with; namely, the lack of reference to Jean Rhys’s novel The Wide Sargasso Sea. A novel written through much of the 1950s and 1960s in rural isolation but which exploded the understanding of the earlier novel as it gave voice to the first Mrs Rochester. Why Gilbert and Gubar leave it unmentioned is a mystery to me, but it is an obvious lack. An absence without easy excuse.

After this upending of the canon’s reception, they moved on to modernist literature, with the three volumes of the aptly-titled No Man’s Land. Again, as someone ‘educated’ in modernism in the 1970s, the revelation that there would have been – in the polemical words of Diana Souhemi – ‘no modernism without lesbianism’ – was revelatory. More accurately, the revelation that the core technique of modernism – the inaccurately named ‘stream of consciousness’ – was both developed and named by women writers, threw my very partial understanding of that writing into new territories. Places where, nearly fifty years later, I still continue to explore, read, teach, think and write. It was their work that gave me this gift.

More than that. Sandra Gilbert, with Susan Gubar, expanded this work still further when they set out to edit the Norton Anthology of Literature by Women; the traditions in English. One more time their work changed perceptions of literary tradition. Here, and perhaps even more challengingly, they argued that women’s writing was there. From the early days. My own days with the Gawain poet, with the Piers Plowman author, with Chaucer were now seen to be not so much lacking as in urgent need to the presence of the writing women who were ignored, dismissed into anonymous obscurity. Their critical work made the oh-so very obvious point, the so-easily avoided point, that women write. And that women’s writing should sit alongside the writing of men.

I have studied and taught and written about literature for nearly fifty years. The earliest years of that seem to me now a time of such partial knowledge that it seems better described as fumbling ignorance. What their work did, in a version of a contemporary anthology, was “split my world wide open”.

Not just their academic writing and work, but also in one moment Sandra Gilbert’s demonstration that academic work is not enough on its own. The commitment needs to travel out. At a time when sexual harassment of students was, if not routine, then certainly common she and a group of colleagues protested the indulgent treatment of a harasser. And then resigned their jobs when the indulgence continued. The details of that case continue to be obscure but at a time when a colleague told me quite openly that he told female students that their marks depended not just on their academic work but ….., their stand was remarkable.

And I haven’t even mentioned her poetry.

Sandra Gilbert was remarkable, in many ways, and I thank her for the changes she brought to my understanding of what has been my life work. That unimportant and yet oddly vital business of making sense of literature.