The Spark

One of my newest and brightest friends in Germany initiated a conversation with me about plans to reform Germany’s citizenship laws. In the best of faith, he raised certain lines of argument which I think are grounded in, to put it kindly, malignant anxieties.

Background

Currently, becoming a citizen of Bundesrepublik Deutschland requires renunciation of your previous citizenship. Germany forbids dual citizenship for non-EU citizens but with exceptions for citizens of Switzerland, Israel, countries that forbid renunciation or people facing persecution in their home states. More than any other requirement, this is the one that is perhaps the most philosophically and practically onerous.

Furthermore, the length of time required for legal residence is 8 years or 7 if you complete an extra integration course (costing about 1500 Euros for 600 hours of lessons over an approximately 6-month period). The costs for German citizenship and integration are very low compared to British citizenship. Visa renewal fees cost tens of Euros, and the application for citizenship is currently 255 Euros plus 51 Euros for each dependent minor. To apply for an indefinite leave to remain visa in the UK costs 2,404 Pounds for each applicant and dependent. Naturalization applications cost 1,250 Pounds.

Seen in this context, Germany’s citizenship regime comes out looking neither terrible nor outstanding; a quintessentially German outcome. So why fix it if it isn’t broken? This is the question asked by many on the right-wing of German politics, including the leader of the German opposition, Friedrich Merz (on the far-right of the Christian Democratic Union). Leaders within the ruling coalition from the libertarian market fundamentalist “Free Democrats take a similar position. To them, it is essential that integration into German society is prioritised and that the value of German citizenship should not be undermined.

The proposals do not structurally change the requirements around integration – primarily achieving competence in the wonderful German language – as political scientist Samuel Schmid argues in his Verfassungsblog. He makes the technical case for these reforms with academic authority that I do not possess. Henceforth, I diverge into a more abstract discussion on citizenship, integration, and the racism that accompanies the expansion of citizenship.

The Constitution of a Qualified Citizen

After reading Perry Anderson’s masterful Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism and its sequel Lineages of the Absolutist State, I realised that the idiom “All roads lead to Rome” is truer than I could have possibly guessed. Contestation of the rights and privileges of citizenship sparked convulsive wars in the Republic, most notably the Social War. Rome’s advance into Germania Magna was halted at the Battle of Teutoberg Forest by Arminius the Cherusc, a Germanic tribesman with Roman citizenship and Equestrian rank. Perhaps one can trace the German reluctance to share citizenship to the promethean event that preserved the very notion of a German people. Owing their very existence to the expression of a dual loyalty, they are uncomfortable with the possible consequences.

That said, I doubt any Turk with German citizenship will lead a confederation of Central Asian Turkic peoples, betray the Bundeswehr, and slaughter three divisions of soldiers. I’d be more worried about the two-timing Swiss.

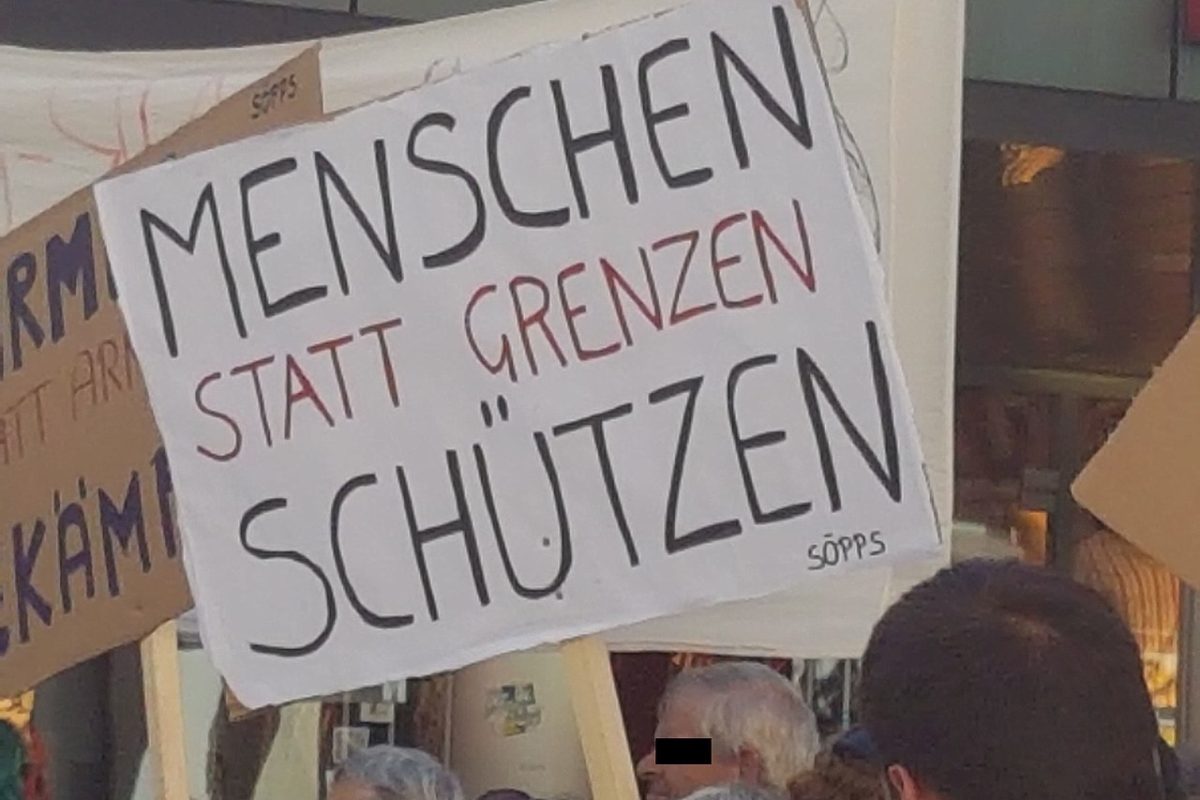

As is often the case, what is not being said carries more salience than what is. Politicians raising “legitimate concerns” about integration and the value of German citizenship are merely rubbing the racist G-spots of their supporters and exploiting latent ideas of German superiority as a battering ram against the most elementary steps towards a modernised immigration policy. No leader of the “centre-right” would have the courage of their convictions to stand up on a podium and declare that citizenship simply shouldn’t be extended to Turks, Syrians, or other Undesirables. But in practical terms these are the very people who they are referring to when they blow dog-whistles about integration and the value of a German passport.

Intellectually, the distance between Donald Trump’s remarks about shithole countries and the remarks from Friedrich Merz or Mario Czaja is about the same as the distance from the shower to the commode; you can’t avoid the smell of shit.

This is illustrated by the (unforced) exceptions to dual citizenship that already exist for EU, Swiss, and Israeli citizens. Once you make voluntary exceptions for 15% of the world’s recognised states any concerns about conflicted loyalties are exposed as the explicitly racist assertions that they are. How is a Turkish immigrant, who came to help build the West German economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder), unwilling to forego citizenship of their ancestral country for sentimental and practical reasons, less trustworthy than an Israeli citizen who has only ever known stealing Palestinian land? What are the particular integrative advantages possessed by Cypriots, Hungarians, or Croats that are lost on people from outside this magic circle of nation states?

Some are born with the benefits and protections of German citizenship. Others enjoy comparable benefits and protections as members of peer states. But the vast majority of us in the world are born in a subaltern class. We, who are born in the proverbial gutters of the world, must supplicate to the masters of our destiny for the recognition of our humanity.

I used to think that civic participation is the finest expression of integrating into an adoptive society. But alas that was my naivete. Little did I know, that those who make the least effort to participate in the civic life of their country are those that are most naturally secure in their citizenship.

Universal human rights to life and liberty, freedom of opinion and expression, work, education, shelter, and food. When we seek them out in states where these are relatively abundant; when we cross borders, abandon our native cultures in the prime of our lives only to toil in the industries of these hallowed lands; navigating their perpetually hostile border bureaucracies and suffering the insults of their mistrusting citizens; it is we who must politely beg to be afforded the full suite of political rights that accompany obedient participation within society.

People often forget that a precondition of naturalisation is the absence of a criminal record. In the particular case of Germany, you have to explicitly accept the Grundgesetz (The Basic Law) as the constitution of Germany. Eminently fair expectations you might think. Yet only last week a major criminal conspiracy of the Reichsbürger (citizens of the Empire) was unravelled by the German authorities leading to arrests of 25 individuals which include a prince (named Heinrich XIII I kid you not), a judge, and a celebrity chef from Bavaria. The movement has connections to the German police, military, and judiciary. They are famous for having their own passports. Will any of these born and bred Germans have their citizenships revoked?

All this without even needing to mention the Nazis which were rehabilitated at the precipice of German society soon after the Second World War. The façade of concern around integration is swallowed by the sinkhole of German contradictions. It was never about integration, only about obedient acceptance of obligations without reciprocal rights of representation.

Towards a New Model of Citizenship

Germany invited people from foreign countries to supply the labour needed to fuel a miraculous recovery from the greatest war defeat in human history. Yet Germany made no promises about being a welcoming environment for the workers that would enrich post-Nazi Germany, in spite of codified promises within its own laws towards maintaining equality. To this day those inequalities and discriminatory norms plague German society. It is clear in this context that no amount of economic or social integration can overcome the burning injustices and inequalities of German society. The solution, as ever is the case, lies not in the domain of language or economics or culture, but politics.

Political representation is a necessary, but insufficient, pre-condition for addressing the structural inequalities that persist in Germany with regards to its 9.7 million (14%) inhabitants with a Migrationshintergrund. Only when the gravity of this mass of unrepresented people is taken into account, will Germany’s political centre of gravity begin to readjust into a balanced position. Paradoxically the political disenfranchisement of nearly 10 million people gives an undue influence to the enfranchised.

Many of the enfranchised do not fulfil their own criteria for integration into German society. For every “non-German” who lived in Germany for years without learning German there is at least one Nazi who wants to restore the Third Reich or a person with a criminal record which would make them ineligible under the current naturalisation laws. Nobody is calling for them to be made stateless even though, excluding their command of the German language, they may be less integrated to the rules and norms of Germany than a Syrian or Ukrainian fleeing war. Nor should they be banished.

Citizenship should be a set of mutual rights and obligations. If that criterion is fulfilled, then those political rights should be granted in earnest. German society itself would benefit in the long term. In the age of transnational capital loyal to no language, culture, or history why should workers be bound to jump an elaborate obstacle course in order to gain political representation? Especially when no amount of learning German or participating in the economic life of society is ever sufficient to be treated as an Echter Deutscher?

Conclusions

I used to play the good immigrant. I used to think less of those immigrants who came over and “abused the system” to give us well behaved immigrants a bad name. Those who spoiled it for everyone. I learned more British history than Brits, I spoke better English than the natives, and I participated in British politics more avidly than any of my peers.

Though I can’t claim to speak better German than Germans, I know more about German history than the average German and I understand the country’s political problems quite well. I used to think that civic participation is the finest expression of integrating into an adoptive society. But alas that was my naivete. Little did I know, that those who make the least effort to participate in the civic life of their country are those that are most naturally secure in their citizenship.

For citizenship is a transactional relationship. It is not grounded in loyalty to a constitution or a set of institutions such as a monarchy. Arminius was not granted Roman citizenship because he spoke Latin or because he learned to “do as the Romans” did. He served in their military, risking life and limb long enough to earn the privilege. When Caracalla extended Roman citizenship to inhabitants outside of Roman Italy he was motivated by expanding his tax base, not spreading the virtues of Roman law to distant lands. The explosion of modern constitutionalism (according to Professor Linda Colley) was grounded in a similar desire to recruit militaries at scales to match Napoleonic France, for the first time codifying rights and obligations of citizenship in foundational documents of modern states.

One might think that this transactional framework is a sacrilegious diminution of citizenship but I say it is the purest form of citizenship. Only a contingent citizenship, one that is grounded in the adequate performance of mutual obligations between state and citizen, is one that can be kept sheltered from the plague of ethno-nationalism. We are far from achieving such a framework in practice. In this context, we could do a lot worse than the slogan of the American Revolutionaries: “No taxation without representation.”

This post first appeared on Ali Khans personal blog. He would be overjoyed if you subscribe.