WE SEE / WIR SEHEN / ΕΜΕΙΣ ΒΛΕΠΟΥΜΕ / אנחנו רואות / نحن نرى is a project conceptualized by artists Adi Liraz and Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman, with Eliana Pliskin Jacobs as a collaborative performer. The multi-site performance between Ioannina, Greece, and Berlin, Germany took place on March 29th, 2024. It was the shabbat evening after the 80th year since the deportation of Liraz’s grandmother. The artists sat, walked, and reflected on the unfolding atrocities in Gaza, repeating “Gaza my love, we see”. It draws on historical imagery of antisemitism in Germany, particularly the blindfolded figure representing a blind Judaism known as Synagoga. The artists insisted on their presence as a protest in the places where their families had been exterminated by National Socialism.

For Adi Liraz, it connected to the murder of the family of her grandmother in Ioannina. For Eliana Pliskin Jacobs, it connected to the murder of her great-grandparents in Berlin. For all the artists, insisting on reflecting upon these histories of violence was essential to protest the ongoing mass killing and ethnic cleansing in Gaza. They gazed through historically imposed blindfolds, to comment on the systematic repression in Germany and beyond – of pro-Palestinian Jewish voices. These demand the right to see their Holocaust histories in constellation with other acts of mass violence, underlining “Gaza my love, we see”.

They wrote that, “Facing the mass killing + ethnic cleansing of Palestinians perpetrated by the State of Israel*, we, carrying these stories, refuse the fascism forced on Jews by Nationalists + Philosemites. You tell us we lie. Thirty thousand murdered; 13,000 children; 1.8 million displaced; 700,000 in most severe starvation; 1.3 million in acute hunger facing it; 70% homes destroyed; 1 million ghettoized in Rafah waiting invasion. You tell us we lie. You tell us burn + bury through infants in incubators, water, universities, hospitals, poets, flour or we blaspheme our ancestors Nelly + Rivka + Annetta + Nissim + Erna + Martin or we’re not ourselves, you blindfold us, Gaza my love, we see you inside ourselves.” Full project statement here.

I was wondering about the historical background of the Ecclesia and Synagoga figures. Can you explain their meaning and how they inspired this latest project?

AL: I work as a freelancer-guide at the Jewish Museum of Berlin. There are two replicas of figures from the 15th century in the core exhibition. A year or a year and a half ago Robert came with a group of students, I gave them a tour and showed them the two figures. Since then Robert and I have conversed about them. Already from the Middle Ages, I think the 11th century, and even before that they appeared in 5th century Rome. Around then, the church started propaganda against Jews using the figures, Ecclesia and Synagoga. This was to promote Christianity by presenting Judaism as backward, blindfolded – and Christianity as a queen looking to the future. Everyone could see them. This further influenced hatred towards Jews that developed into actual violence against Jews.

RYS: We thought about Synagoga as one part of an ancient racial imagination of Jewish blindness. There’s a 13th century public engraving on the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, wherein Jewish men are depicted suckling a pig, while one opens and stares into the animal’s anus. The image references a sermon from Martin Luther, declaring Jews find the Talmud inside a pig’s anus; the Talmud, being, as Daniel Boyarin has written, that which “maintained a diasporic existence.” To us, this “Jewish Sow” image was also one on Jewish blindness. A German convert to Judaism in recent years sued to remove the engraving. Historical preservation laws prevailed. Adi and I took a position that such public imagery should remain, yet accompanied by some form of permanent, if changing, intervention, because it evidences a deep, thousand-year legacy buried in a contemporary German discourse that isolates Nazism in history, culture, and power. But the roots are so deep and the visual discourse, on blindness in this case, remains potent.

AL: To contextualize this within contemporary discourse, most often when you hear the word antisemitism, or hate against Jews – in Germany it is almost always in connection to refugees from Muslim countries or Palestinians. In a way it seems like German society is trying to push away their own responsibility for the deep-rooted hate against Jews within its own history. The word anti-Semitism comes from Germany. Of course we cannot deny that anti-Semitism also exists in Muslim countries. But this is actually something that was reflected from the colonial projects of Christianity to either convert other people to Christianity or conquer and occupy Muslim countries. That brought with it this idea of the Jew as powerful, rich, conspiring. We tried to reflect on that in this work.

RYS: And to use the figure actually as a performer: to take the statue from the museum to the streets. To re-inhabit that figure in order to create a visual, ethical, cultural intervention in the contemporary landscape.

I found it really interesting how multi-sited your interventions were, between Greece, Ioannina; Germany, Berlin; referencing Palestine, Gaza; and enacting memory-scapes stretching back generations and histories. How did these physical and memorial places come together for you all: for Adi and Robert as the work’s conceptualizers and for Eliana as a performer?

EPJ: I think that one of the most interesting elements about this performance is that it looks across so many spaces, especially towards what’s happening in Palestine and also seeing inside ourselves. It was very powerful that Adi and I were doing the same thing at the same time in our – as much as Jews can call it such – ancestral homelands. I found this spanning a very powerful part of the work.

AL: For me, the core of this work is commemoration of different violent events in which people are being mass murdered or ethnically cleansed. I don’t think there is a justification for competition between who has suffered more. It’s possible to feel several things and not only one pain. When we look at the 80th commemoration day of my ancestors in Ioannina, I can also commemorate the expulsion and murder of Eliana’s great-grandparents; and the contemporary violence acts against the population in Gaza.

RYS: What you called a multi-site performance, Sarah, is connected for me to the idea of how we perform our diaspora, or diasporas in the plural. Because Jewish history contains multiple diasporas. The bifurcation of our world into exile and Israel is a Zionist narrative. When we perform in multiple sites, we pull traditions from those sites and cultures. We serve our diasporas, we perpetuate our diasporas. We say: We live, Jews live.

EPJ: Within Yiddish-speaking communities of Eastern Europe there was a very strong concept of Doikayt, meaning “hereness”, being here. Zionism as the default mentality of Jews was only imposed on many Jewish communities after the Holocaust. Before, there was a widespread cultural pride in diaspora, at least in the Yiddish community of Eastern Europe.

AL: Just to add on to that, the National Socialists argued that Jews do not belong in Germany and need to go to Palestine. So actually there is a strong connection between imposed Zionism and National Socialism. This is the significance of working here in Ioannina for me. Because it used to be Ottoman for such a long time. But dominated by a Muslim empire, it welcomed and even invited Jews to be part of it. But I do not ignore the atrocities committed by this empire towards other populations and later towards Jews in Turkey.

In the six months since October 7th, how do you feel about doing this recent artistic work in an atmosphere of increased pro-Palestine repression and silencing of speech? Where do you think artistic actions fit in this space?

AL: Pari El-Qalqili and Nahed Samour argue that political art or the arts in general, cannot exist anywhere else in the moment but in the street. In Germany after October 7th, there is censorship of critical voices. So the only place to actually reflect critically is on the streets. Many people are not talking at all or are very selective with their words, especially people who don’t have German or European citizenship. We can also think about the meaning of protests. There are demonstrations, which often end with a mass arrest – and there is a kind of protest through creating interventions, using different kinds of materials and tools through art. In a way there is more freedom of speech in these kinds of actions. So if we look at it from the perspective of protest, there is more possibility to express and create criticism through art. If we look at it from art institutions, it is more possible to be critical out on the streets – than in the institutions themselves. Since October 7th, in the institutions is such a strong censorship and repression.

EPJ: As Adi mentioned, everybody’s scared, but nobody actually knows what would happen if you step across the boundary. I think there might even be more leniency than we’re aware of. For instance a large Jewish institution in Germany (name redacted) liked our Instagram post about the project. I think the only way to find out the boundary is to push against it gradually. Conversely, I think there is absolutely no discourse in Germany, or in the rest of the world now, on what is going on right now within a larger historical context. Perhaps it’s too present for people to step back and see historical phenomena in perspective. But I wish this were addressed even in demonstrations in Germany. Both in terms of Germany providing weapons for Israel and providing the enormous spark that eventually led to all this in the first place.

RYS: I think that if we were able to have an informed and truthful discourse around this—the ties between the Holocaust and the ongoing Nakba—it would be different. We would all be different. Honestly, I see a lot of antisemitism at demonstrations. I’m sorry to say this. I’ve seen signs that read: “Zionists are indigenous to hell” and “If you love them so much why don’t you give them your land”. These phrases mask earnest widespread anti-colonial and humanitarian desperations that I share. And they scald the very pulse of the extreme vulnerability and volatile relationship to land and politics Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews have bore over the past thousand years. It is a vulnerability and volatility that is at the root of this cycle of genocide we see tearing our world apart today. I think it’s because we can’t have this conversation nearly anywhere that there’s so much personification, radicalization, and mystification of its trans-generational roots and trajectories. It’s as if at once Jews were the only victims that ever existed but now (as Zionists) they’re the only perpetrators. Between them Nazism forming this bridge of exceptionalism. But Palestine/Israel is part of the former Ottoman Empire, the slow dismantling of which, over centuries, constituted multiple genocides and ethnic cleansing campaigns from every ethno-sectarian direction. The catastrophe of Palestine/Israel extends all these histories.

We’ve touched on repression in Germany as well as other places. Alongside this, at least as I have observed within leftist Jewish contexts in Berlin and New York, there is often a discourse about the privilege of being Jewish. Namely, that Jewish people have some leverage to not get punished as badly as many more precarious people intervening. They can use their status as a model minority in Germany to intervene, particularly to help the Palestinian cause. What do you think are the potentials and pitfalls of intervening as a Jewish artist in Germany?

AL: There was a time when I thought I was protected in Germany because I’m Jewish and Israeli, and then I learned that this is bullshit. Of course, in comparison to other discriminated groups we´re more privileged, but it’s not like we are protected. We can also be accused or lose our access to certain things when we become too vocal about some topics. Each time when we say things that do not fit into the “Jew box”, are not well digested, we can also be excluded.

EPJ: And I might add that the idea of the privileges of being Jewish in Germany are based in discrimination, in stereotyping and generalizations about a particular desired kind of Jew. Germany wants to protect its Jews but it wants to protect its good Jews. There are a couple of bad Jews – let’s just push them to the corner and not listen to them.

RYS: I think we need to say that Palestinian-Germans and peoples, in this context, especially Muslim and Arab, without papers or with precarious papers, of course they’re always more vulnerable when demonstrating, when making statements, when doing the kind of work that the three of us feel more or less able to do. When we create such things in the streets of Europe we are thinking about their circumstances and trying to enact a solidarity with them and their families.

Where do you think the use of certain terms, words, or terminologies fits within such solidarity and broader possibilities of artistic intervention, especially in German spaces? In this recent project, you all had a lot of debate over whether to use the word “genocide” to describe what is going on in Gaza. It is not about a lack of information or disagreement with this term to describe what is going on, but rather about a climate of fear and intimidation when people use this word in Germany, alongside a broad lack of contextualization and discussion.

AL: Yes, earlier we were talking about fear, also of certain terminologies, these things are also dynamic. Some things that we were able to say before October 7th became forbidden afterwards. Some things that in the first couple of months after October 7th were forbidden are now allowed. It’s constantly changing. The only thing that is stable is the fear put on us from Germany. This causes us to doubt and rethink how we express ourselves and the use of the word genocide. I have read the official definition of what the German government considers genocide so many times. Each time I read it, I don’t understand why it does not apply to what is happening right now in Gaza. I was afraid to use it until recently because of the fear of what could happen to me. We had a conversation around whether to use “genocide” in our project description because we both have certain ideas and are afraid and trying to protect ourselves. It’s ridiculous because we are all Jews! Eliana and I have ancestors who were murdered by Germans in events defined as genocide in the official definition, and yet we are afraid to use this word. It’s ridiculous.

EPJ: Precisely. We are afraid of accusations of anti-Semitism, which is absurd. Because we are using this term in the context in which we are talking about our great grandparents who were murdered by anti-Semitism. The descendants of those who murdered them are now accusing us of committing the same crime (“anti-Semitism”) that their great grandparents did to murder ours. They put the responsibility of their own crimes and atonement onto the descendants of their own victims.

AL: This is what our performance is about. They put the blindfold on us, they try to blind us, but they don’t succeed.

RYS: And we see through other means. Why are we doing this? Why have we been yelling about these things along with many other Jews and Palestinians and non-Jews and non-Palestinians for years, decades? From a Jewish perspective it’s about the integrity of our ancestors. We don’t want to see our ancestors and the crimes against them used to justify or obfuscate the crimes against other people. This is a horrible, violating feeling. After receiving the violence, there’s very little that’s worse than this.

This recent piece connects back to both of your broader artistic practices and their motivations. Robert, there are intersections with your recent action in Warsaw with Joanna Rajkowska, and your different walking actions in Berlin. Adi, this connects to your project Asking for Nelly (2019), a walk in Ioannina about your grandmother’s younger sister. It links to Megorashet (2022), a walk in Heidelberg reflecting on the city’s entanglement with Greek symbols and German nationalism; and Alle Erinnerungen fließen ins Meer und wieder raus (2021) an action of remembrance of three German-speaking poets, May Ayim, Semra Ertan, and Rose Ausländer. In your works, there are intersections with walking and rituals of commemoration. How are your broader bodies of work in dialogue with this recent collaboration?

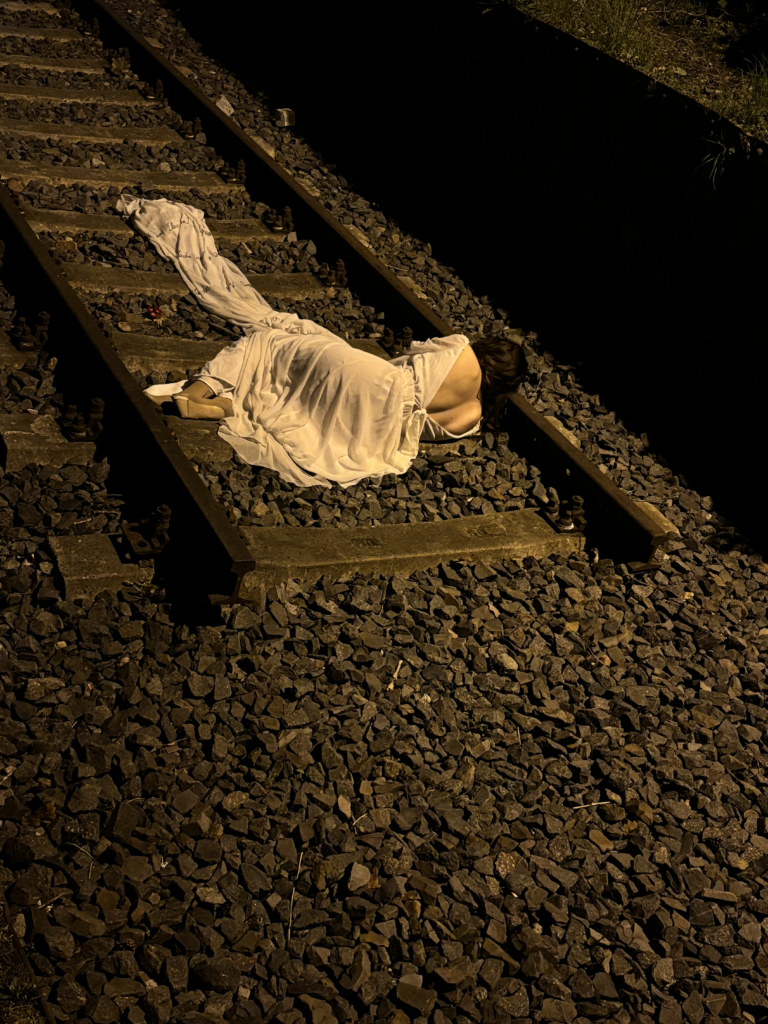

AL: Yes, it directly relates to Asking for Nelly, which was in Ioannina five years ago shortly before the recent performance, March 25th. It was the 75th commemoration of the deportation of the Jews of Ioannina. Five years ago I was walking while wearing a similar dress and holding a projector that projected the image of the sister of my great-grandmother, Nelly. I walked from the place where the deportation started, through the synagogue, to the family´s house. This time I wasn’t walking, I was sitting. I sat because I wanted to look through the blindfold to the location where the Jews of Ioannina were deported from. I wasn’t walking – but looking. Many of Robert’s and at least one of Eliana’s have commonalities, with elements of commemoration, public rituals, aiming to receive solidarity from the audience. For me, this is one of the main reasons why I create art in public space. But it’s also about accessibility, about bringing communication and storytelling to people. To create the possibility to learn and interact not only by going into prestigious institutions. It’s also a spiritual experience; people are feeling very connected and there are moments of exchange, of learning and of communality.

RYS: I felt honoured to have created this piece with Adi. This is our first significant collaboration. My family was not deported or murdered in the Shoah, but were exiled during the Pogrom era in the late 19th century and early 20th century. I felt moved to work with Adi and Eliana in the exact sites where their families were deported to their murder in order to together protest for life. It was a very intense practice. I realize it follows the trajectory I’ve taken in recent years; that is a process of poetic mediation, in helping others imagine a way through tumultuous conditions of memory, violation, and land. Adi and I have created a visual language with the blindfold. It is a potent supplement in its context, and I think could be used by others to cut through the imprisoned yet urgently necessary discourse of the Holocaust and the Nakba. It is a kind of public performance that reaches quickly and deeply into mold-infested undercurrents of social imagination which fuel today’s atrocities. It reaches to find another language, to transmute this violence.

Thank you all for sharing your thoughts. Any final words?

ESP: I condemn Germany for using their murder of our great grandparents to justify the murder of countless more today. For putting the responsibility of atonement for its own genocide onto its own victims. And for turning the lesson that it should have learned from its past – never again shall there be systematic extermination – completely upside down as it now supports systematic extermination. I urge the German public to recognize the inherent diversity of Jewish discourse, and to hear the many voices of those of us who cry “Stop supporting the killing of our sisters and brothers!”