“The last two weeks… It kind of created a disappointment for me towards the West. Especially because these countries are, especially us as Arabs, we aspire to go to because we can have freedom there and we can do whatever we want. But since seeing that there is this hidden racism and there is this, uh, control of speech… I used to think, you know, the West is really experienced with humanitarian things, but they’re really experienced with humanitarian things that are for white people.”

(Zababdeh, 2023).

It was in the closing of our interview that Zababdeh shared the disappointment that he felt about the West’s response to the genocidal violence taking place in Gaza and the ethnic cleansing in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Zababdeh’s was the first interview I carried out with Palestinians in Amman, an overlooked part of the Palestinian diaspora whose stories [if they are told] are often framed through a limiting and orientalist lens. The six interviews which took place in the third week of October aimed to capture the mood in Amman. The interviews – which started by simply asking “how did you wake up to the news of October 7?” – very quickly became narratives about this disappointment and failure of the West.

“And I couldn’t breathe because I know the West, I know that they are a bunch of criminals, it’s not that. It’s just, it’s the world that we live in has been forever and until this moment so unfair.”

(Dawaymah, 2023).

As the interviews continued and I listened to the shared stories of disappointment, frustration, and fatigue it wasn’t sadness I felt, but rage. Whilst at the centre of these stories were political systems and media, I could not help thinking about the academy. It was as if the interviewees were talking directly to me about the failure of academic institutions, particularly when reflecting upon Al Quds’ description of these weeks:

“It goes from anger to hope to rage, to feeling dismissed. It’s insane every other day…my profile is not even public. It’s a private profile with my friends on it. Why the hell would you shadow ban me and they’re, like most of them, are Arabs? So going through those emotions of being silenced, it is all about feeling dismissed. Yeah, you are dismissing a whole population. And that’s the scary part, you know? It feels like, am I missing something? I mean something in the history of Palestine that we fucked up. Like did the Palestinians do something so bad, worse than the Holocaust, for us to be dismissed this much?”

(2023).

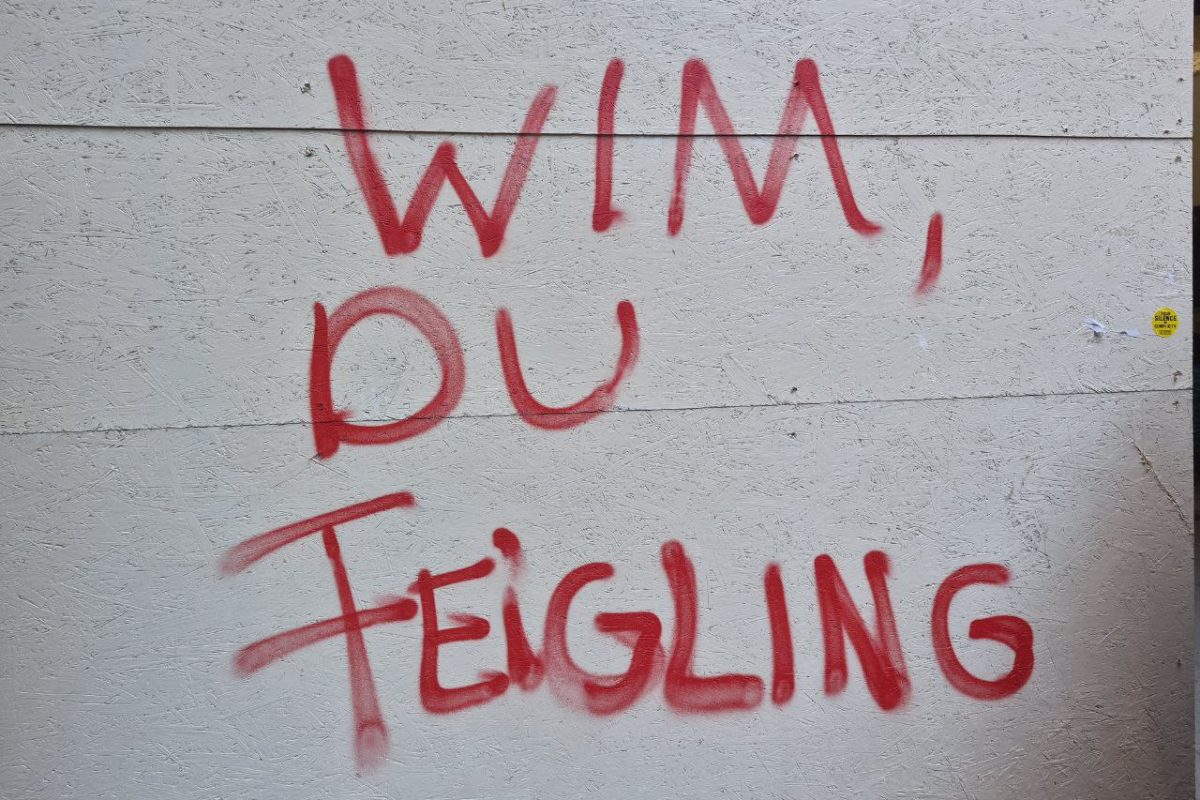

Listening to these stories, it would have been easy to put the focus on all the other agents at play, but in every research encounter, I think each of us has a duty to ask: “what is my role in this?” I felt enraged because dismissal is something that scholars can help to limit, to remediate, and to do so with a historical contextualisation to guide readers in a way in which the media cannot in its desire for fast stories. I think it’s why I have been so shocked at both the silence and silencing taking place in higher education institutions not only in the Netherlands, but globally. It has left me with the same feelings of disappointment, frustration and fatigue. However, I don’t want to use this space to reemphasize how academia has so far failed Palestinians during this crisis. Instead, I urge you to respond to the clarion call that emerged from these interviews in Amman and to take heed of these three things: urgency, agency and rage.

Urgency

As a doctoral candidate within a Heritage and Memory Department, I’m part of an academic collective which praises itself for being at the heart of understanding conflict heritage. It’s a realm in which scholars constantly assert that we look at heritage not to understand the past, but to understand the present. However, the current intellectual atmosphere is one where if Palestine is discussed, the conversation is quickly steered into a realm of depoliticization. I know many of my colleagues are more confident working with “oral history”, but we are witnessing unprecedented levels of erasure of lives, ecology, cities, and more. This is the time for each of us to step out of our comfortable and secure spaces and to be writing about Palestine now – not waiting for the oral histories of these events to emerge before writing. On November 29th, many of us will be uniting for the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, those of us in the Dutch higher education sphere are demanding the right to openly teach about the history of Israeli occupation and apartheid without intimidation. Whilst there has not only been silence from many scholars, there has also been a terrifying level of silencing (and policing) of those of us speaking out. Thus, I also call upon comrades who can support scholars to get our work out through different mediums – if our institutions silence us, I make an urgent plea for journals to help us by publishing at least through a blog form as soon as possible.

Agency

Palestinians do not need you to speak for them, and they have never needed anyone to do so. What is required though is to ensure our writing and our teaching supports Palestinian agency rather than diminishing it. The traps that have been laid for decades in the European institutions – with voice and power in the wrong place have not disappeared. Moving forward we need to make a simple change in words, but one with huge reverberations. We must remember to learn from Palestine, and not learn about Palestine. As learning communities, we need to centre Palestine (and Palestinians) not as a subject to decades of colonial violence but as an agent in which we can actively learn from. We as scholars have a responsibility to produce scholarship which disrupts popular language surrounding Palestinians in their abstractness or as mere numbers – this is critical. If we as scholars do not disrupt these narratives, then we play into one of the weapons being utilised by Zionists and the media whereby dehumanisation is used as a tool to suppress and censor Palestinian stories – promoting a narrative that Palestinians are subhuman and thus, less worthy of space and voice. I urge you to think seriously about the question: where is the voice and power?

Rage

These are abnormal times. It’s not on over-exaggeration to state that there now seems to be a pre-Oct 7 and post-Oct 7 world. Whilst violence against Palestinians is not new, this event has truly shocked many who’ve been engaged with the long history of Palestine – never before have we had access to watch and witness genocide. We carry these violent crimes in our pockets -watching these acts feeling helpless and questioning our capacity to do something, filled with a huge sense of sadness and guilt over the injustices. However, I urge you to change your response. Do not be part of the resistance because you feel sorry for the plight of Palestinians. Palestinians do not want your sympathy; they want your action. When we feel sadness and guilt we tend to close off and move away from actions. As Wendy Pearlman writes these are disempowering emotions. Instead, listen to these stories and feel rage. Let rage empower you to listen to the stories of Zababdeh, Al Quds, Abasan, Yaffa, Dawaymah and Abu Dawaymah and take action. Do not take these stories to be part of a narrative of the events of October 7 that we will study in history books, but stories to act upon. Our institutions are telling us that to have rage is to bring about an unsafe environment – it’s not. It’s that our institutions know that when we have rage, we are empowered to we act, and we do. Allow these feelings, lean into them, and act upon them.

Me: “How would you describe what you are witnessing right now to your nephew?”

Yaffa: “I will tell him that we tried to fight for our existence, tried to fight for our dignity.”

There’s not much left to say when you listen to Yaffa’s words aside from urging you, as fellow scholars, that we have a duty to actively challenge those who continue to dismiss the voice of Yaffa. Instead, respond to this clarion call and the need for urgency, agency and rage.

All interviewees named have been changed to pseudonyms – the pseudonyms play homage to the origins of those I interviewed as a way in which to keep the names of Palestinian towns and cities alive.