When I first moved to Germany, I remember being initially puzzled by how people could be experiencing financial hardship here. Tapes from my Malaysian-Chinese context were on play — you have a welfare system, a state that actually has a social safety net to catch you when you fall. Do you know how lucky you are?

My initial perception of the EU powerhouse was that it was ‘stable’ and ‘socialist’ — worlds away in progressiveness from the places I had previously lived. Whether it was unemployment, pension, childcare — you were on your own, especially as an immigrant. But this was slippery slope thinking, according to which simply having a welfare system would mean everyone in a country was able to succeed. The story would then continue predictably: if people don’t climb out of poverty or unemployment with social support, especially in a country like Germany, it would definitely be due to a personality problem. People are doing it to themselves.

As someone who considers themselves embodying the values of the political left, I surprised myself as these thoughts came to me. Neoliberal meritocracy is the dominant global value system today. Far from being just a detached political narrative, it’s deeply embedded in our consciousness and is dominant in the German public and political mind. It finds itself in public debates about Hartz IV (Arbeitslosengeld II) & Bürgergeld reforms, how institutions like the Job Centre run their services, and around whether immigrants are deserving of help.

Evidently, these narratives were also internalized in me. I had spent so long defining my own right to belonging by the economic standards of being a ‘good immigrant’. So, I decided to dig past my own resentment of never having lived under a government that felt ‘compassionate’ – and understand that the reality of why inequality existed was much more nuanced than that. Under the current climate of employment uncertainty, I wanted to see how ‘the best welfare system in the world’ catches people when they fall, how it fails people, and how our ideas of ‘success’ could affect our own psychological beliefs about who truly deserves help.

The Trauma of Welfare Stigma

Germany’s welfare system has long been admired. It was heralded for being the first nation-state social security system. Unlike the US, it is a state-managed system relatively untethered by corporate interests. It ranks as one of the most generous and comprehensive welfare systems in the world. I was a grateful recipient of German welfare during the pandemic when I first moved here, it remained an important lifeline for me on my way towards finding stability. However, it is not something to be unanimously celebrated.

One of the most commonly discussed and controversial welfare policies was Hartz IV, a colloquial term for Germany’s former unemployment fund (Arbeitslosengeld II). Hartz IV helped to trim down Germany’s unemployment rate by 50%, but also quickly became associated with heavy stigma towards the working class and immigrants.

“As a research assistant at the Fraunhofer Institute a few years ago, my colleague asked me a question that I’m always terrified of: “what is your mother doing?” For the first time, I felt confident enough to be vulnerable and told him that she is unemployed and receiving Hartz IV. His response was one that I’ve heard before: “Oh, really? Why?” I explained that my mother was a single parent who came to Germany from Turkey and worked in seven different places before being let go because she had to pick me up from kindergarten. She couldn’t find a job after that, so she decided to be there for me. My colleague proceeded to express concern about his taxes going to people like my mother who he believes are taking advantage of the system. This is a common narrative that I have to deal with, and it hurts every time. The truth is that many people who receive Hartz IV are not taking advantage of the system.”

-Sue Sarikaya, Head of Diversity & Inclusion at The Dive

Sue was far from alone. A study found that the levels of shame felt by recipients of German welfare increased with the amount received. 40% of recipients who didn’t work for more than two years reported feeling ‘completely’ or ‘somewhat’ ashamed of receiving benefits.

My German friends told me they had all grown up with reality TV shows like ‘Die Hartz IV Schule’ which voyeuristically followed children of recipients into their schools and homes, creating a tasteless, sensationalized story around poverty, and the laziness that underlies all the unmotivated people who fell through the cracks.

The story of failure due to personal failures is embedded globally. I surprise myself by finding the remnants of the American Dream even in Germany — a story that no matter who you are, you could make it with enough hard work and dedication. However, this narrative relies on a fracturing from our social context. Where we come from, our own histories, how others perceive us, and who is around to help us. And it is this fragmentation from self and identity that casts out discussion around structural violence. It makes it easy to do a mental one plus one equals two — that marginalized communities are failing because they’re not choosing to work hard, or have regressive cultural norms.

Stereotype endorsements are so powerful, because they are not only reinforced by governments and media, but also by regular people onto each other. Another German friend told me she decided to take up welfare as a newly single mother, and was shamed and accused by her own working class parents for not working for her own money. She was only 19.

Was it failure of the individual? Or the system?

How personal and emotional vulnerabilities intersect with structural inequalities is an understudied phenomena. The world of social psychology rarely intersects with the rational-first economic worldview. Underneath so much of what popular media assigns as ‘lazy’ are people with situational constraints and chronic emotional stresses. The laziness narrative also leaves out the care of lone mothers and fathers, pensioners, the social exclusion of disabled people and immigrants, and the vulnerability of those psychologically struggling. These are the people that make up two thirds of those who are ‘long term unemployed’, who many German politicians repeatedly attack for being unable to get out of the welfare system.

As of 2022, 14 million people in Germany were living in poverty. I always found this hard to believe. “But,” you might say, “this is the fourth largest economy in the world!” It’s easier to understand when you delve deeper into the spoken stories of people, particularly East Germans and those with a migration background, or walk into certain areas. Germany’s wealth inequality is also hidden beneath its facade — 99.5% of the wealth rests in the hands of the top 50%.

Poverty and inequality are associated with higher likelihood of trauma, whether childhood, historical, racial or intergenerational. Chronic economic stress and trauma are also correlated with higher likelihoods of addiction, adverse childhood experiences such as domestic violence and neglect, as well as racial and social discrimination. These factors play a reinforcing psychological role in our self worth and ability to economically and socially participate.

The German education system is often criticized for perpetuating inequality from an early age, such as through early tracking of students to place them into different school types based on their academic performance. Children with immigrant backgrounds are often overrepresented in lower-performing schools, critically disadvantaging them from being able to be admitted to universities. “My Turkish best friend told me she was in my year in school, but I just never saw her,” my German friend tells me. “It took me years to realize she was there, just segregated from me completely.“ Racism also remains a significant issue in Germany. Hate crimes, discrimination, and racial profiling are not uncommon. Financial inequality is also associated with a lack of relationships providing connections to opportunities, which is critical to our success.

What’s missing from the story? Commonly cited reasons for inequality include inadequate food or resource distribution, extended periods of unemployment, discrimination or debt. These are well-known and defined, and yet, also contain decades of debates around why so many interventions have failed. Most development initiatives focus on material distribution – just giving people more food, more money, more opportunities. But just as the meritocracy narrative does, the economic tools used in welfare also largely ignores engaging with our multidimensional reality. By engaging less with our social context, it unironically creates less capacity for self and community development, reinforcing the very dependency it criticizes.

Hartz IV vs. Bürgergeld

German bureaucracy has always had a tendency to prioritize managing issues rather than building capacity. The slogan of Hartz IV has long been “Fördern und Fordern” — sure, let’s support the unemployed, but let’s also make fierce demands on them to get out of their situation as fast as possible. In other words, motivation through fear.

Hartz IV was grossly controversial for barely keeping people above the poverty line. When taken with other government support systems like child allowances and housing benefits, Hartz IV would make percentage cuts on the amount given to recipients. Every additional euro earned would therefore be subtracted, which left some recipients, including my friends and their families, in further precarious situations. Hartz IV would also punish or threaten recipients with sanction cuts on housing, heating and health insurance if they did not comply. It placed no forgiveness onto people who missed meetings, who were overwhelmed with stress and relational obligations, a stark reality for those living in financially scarcity. In 2018, the highest percentage of sanctions were imposed on under 25 year olds.

Hartz IV’s harshest critics also blamed it for being the reason for widening inequality, as the Job Centre quickly pushed people back into work, even if it was low paid with poor working conditions, corrupting an individual’s opportunity to re-invent themselves into something potentially much more harmful. A 2017 study also found that the level of service that the Job Centre gave towards Turks and Romanians had significantly lower quality. The same is found towards EU migrants, due to language barriers.

Today, after decades of calls for reform, Hartz IV has been replaced by Bürgergeld. It has reduced its punishments on recipients, preventing the Job Centre from imposing more than 30% sanctions. It has lowered application requirements, made it easier to apply for education certificates, and slightly increasing its allowance to adjust for inflation. However, many argue that the €53 increase does nothing in light of the current cost of living crisis. Those living in Germany will know how little money would be left after the total €502 is spent on basic necessities like groceries and transportation.

Predictably, the policy has been met with resistance. Centrist and conservative political leaders, such as Markus Söder, framed the higher ‘handouts’ and reduced sanctions as an impossible way of motivating people to get back to work. In a public debate on Bürgergeld, CDU party member Kai Whittaker stated that “Solidarity is not a one way street. The overwhelming majority in Germany say that we should help those in need. But the return is that you should get work as quickly as possible.” These narratives not only frame the structure of Bürgergeld, but also continue to perpetuate the same old story.

Reclaiming our full human experience

Reimagining welfare and the narratives that accompany it requires a profound shift in our beliefs around how people not only survive, but come to thrive.

Financial incentives and sanctions are effective in context, but in the face of something as multidimensional as poverty, can be like dangling a carrot in someone’s face and hitting them with a stick when they misbehave. It doesn’t engage with the depth of what it means for someone to feel strong again after crisis – to be able to go out in the world to pursue the things that empower them. Thankfully, the Bürgergeld debate is not without more holism. Critics advocate for the Job Centre to take a stronger role in supporting individuals with human mediation. What actually helps people get out of poverty? There’s a myriad of proposals that vow to solve the problem, but I’ll share my favorite.

In her debut book Radical Help, UK-based welfare reform activist Hilary Cottam proposes the solution of community. After a 10 year experiment with building social infrastructures with marginalized groups in London, Cottam concluded that capacity building through promoting really seeing and being there for each other was the most effective and long lasting means of helping people thrive. ‘Radical Help’ highlights a possibility of collaboration between public service providers and recipients co-producing solutions, based on contextual community needs. By engaging people and what they struggled with directly, choosing to invest in their potential rather than mitigate risk, she states that we can create long-lasting change that not only catches people when they fall, but gives them enough strength to take flight.

Cottam’s proposal reminds me of my own economic struggles and how I’ve overcome them — a marriage of progressive social policies and reciprocal relationships that allowed me to find opportunities and retraining when I couldn’t find the right work. Meritocracy tells individuals it’s all up to them to succeed, but it leaves out the fundamental aspect of community. It seems so simple, but good relationships are fundamental. My friend Saskia tells me she wouldn’t be where she is today – being able to confidently step into a job with higher pay than her entire family has ever made — without the presence of inspiring women around her. “I know that if they can do it, I can do it too.”

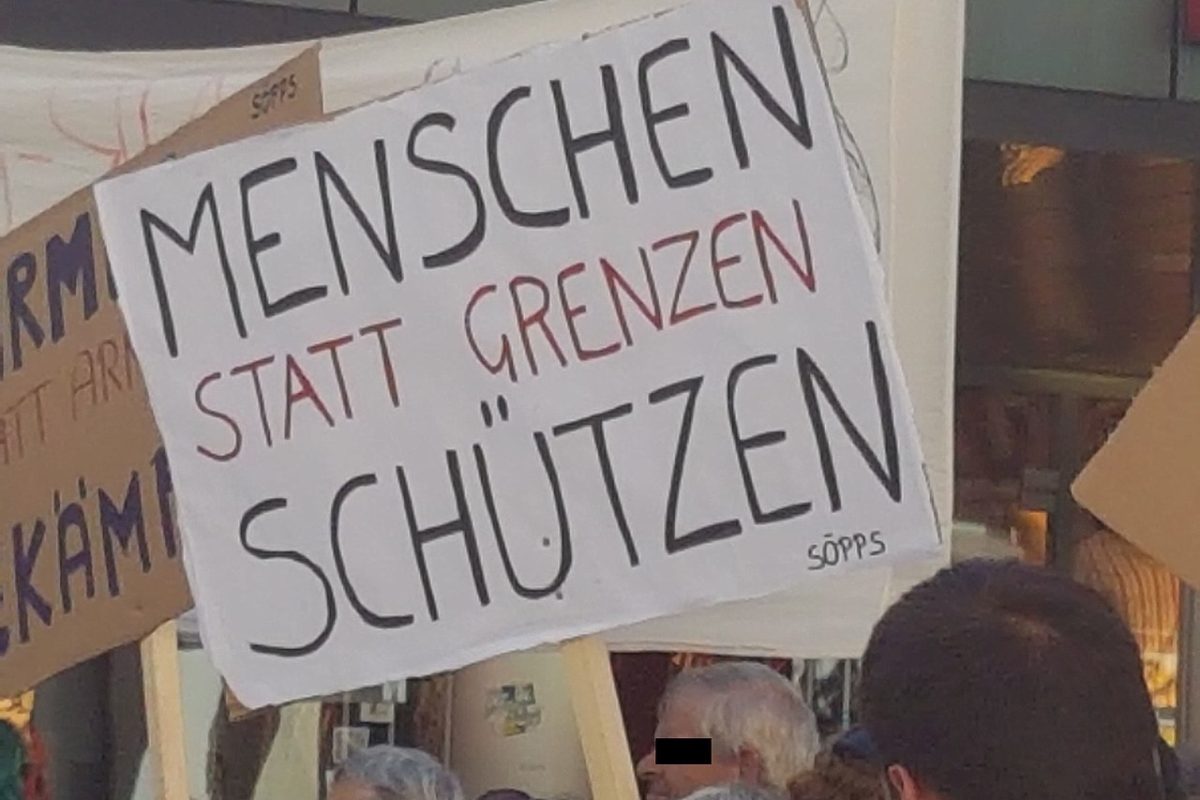

We’ve been told the wrong stories. Wrong empirically, wrong emotionally. This doesn’t mean we should stop helping people with material needs, but we need to put our survivalist assumptions aside and look deeper. One of the greatest evils of neoliberalism is how we come to believe that we are worthless if we can’t meet certain economic standards. Beneath most ‘economically-struggling’ people are stories of attempts, complicated internal and external circumstances, cycles of stress and isolation. Welfare stigma doesn’t just hurt individuals, it also pours into further reform efforts. Around the world, attempts to create stronger welfare support receive backlash from the public around the fear of societal laziness. A study reported that European supporters of UBI demand a caveat on the universal by making strict eligibility requirements for immigrants. I don’t blame people for these views — our collective participation in the economic still remains an emotional symbol of personal survival. But these stories need to change, if we are to be able to adapt to the uncertain realities ahead of us.

What kind of an alternative would we be offering ourselves if we looked deeper into the experiences of people, and what they really needed? Would we be able to reclaim our inherent altruism, believing that everyone deserved help regardless of perceived laziness? What kind of help would we be giving if we brought the full human experience back into the story?

This article is dedicated to my friends who have touched me with their stories, and inspired me with their strength. I am also grateful to Brett Barndt, who taught me that emotional is how you engage people with money & economics, and my close friend Tarn Rodger Johns for giving me ‘Radical Help’ by Hilary Cottam — reminding me that community is always the answer.