The Central Council of Jews in Germany is supposed to represent the Jewish community. Yet their right-wing, racist views aren’t necessarily shared by the majority of Jewish people in this country.

On January 28, the German Jewish newspaper Jüdische Allgemeine published a disturbing article: “Gaza’s civilians not innocent.” This unabashed support for war crimes was authored by Tobias Huch, an eccentric and unsuccessful German politician with no connection to Judaism. Yet it was published in the official organ of the Central Council of Jews in Germany. Such terrifying racism could be seen as representative of the Jewish community.

The “Zentralrat” is recognized by the German state as the official representative of all Jewish people. In reality, it represents 104 official Jewish communities organized around synagogues, with a total of 92,000 members. Let’s crunch the numbers.

The Council is only open to Jews with matrilineal Jewish heritages. As Wieland Hoban has explained, the rules state that “solely the child of a Jewish mother is Jewish by birth, and patrilineal Jews must therefore convert before they can be appropriately considered Jewish.” This means that a person with a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother would be recognized as a Jew by the Israeli state — but is not counted as a Jew in Germany.

Despite the notorious difficulty of defining who is Jewish, estimates put the number at around 225,000 in Germany. In other words, the Central Council cannot even claim to speak for half of Germany’s Jews.

Joseph Schuster, the Council President since 2014, is a conservative politician who has called for “upper limits” on migration — a position he shares with the German Right. Schuster and other Central Council officials tend to come from the small community of assimilated German Jews. They do not only tend to hold conservative views: As Emily Dische-Becker has explained, since Jewish life in Germany always feels so precarious, they also identify much more strongly with Israel than Jewish people in the U.S. do.

Yet this sector makes up only a tiny fraction of Germany’s Jewish community today. Starting in 1991, Germany allowed Jews from the former Soviet Union to immigrate with relatively few formalities. Just over 200,000 “contingent refugees” arrived before the law was abolished in 2004. (That law, by the way, was changed due to pressure from Israel’s government, which was upset that more post-Soviet Jews were moving to Ashkenaz than to the Erez Israel. The SPD and the Greens made it far harder for Jews to immigrate — a reminder that the Israeli state does not have the same interests as Jewish people!) These post-Soviet Jews now make up some 90% of the Jews registered via synagogues. Politically, they are all over the place, from urban liberals to Putin-loving AfD supporters. Some have a strong connection to Judaism, while others never considered themselves Jewish except for purposes of immigration law.

In the last 15 years, thousands of Israelis have come to Berlin. It’s impossible to say how many there are, since most of them have European passports, but estimates put their number between 10,000 and 30,000. Walking around Neukölln, an immigrant neighborhood that is often demonized as a hotbed of antisemitism, it’s hard to miss people speaking Hebrew. This relatively new Israeli community tends to be left-of-center: some of them are militant anti-Zionists, while others see themselves as “apolitical” and simply needed to escape the oppressive right-wing climate in Israel. They have diverse views on Zionism — but it’s noteworthy that the German press has not reported on any Israelis returning from Germany to serve in the IDF’s genocidal campaign against Gaza.

Finally, Germany is also home to Jewish immigrants from the rest of the world, including lots of young people from North America, South America, and Europe.

Adding these numbers up, there will always be some uncertainty, but it’s clear that the Central Council does not represent the actually existing Jewish community in Germany today. And even for the minority who are official counted: electing leaders via synagogues is not a good method to define political positions. There is no lively debate at religious services, and politics are discussed by opaque structures behind closed doors. The Central Council is more like a German government agency, financed by the state in order to manufacture Jewish support for German imperialism.

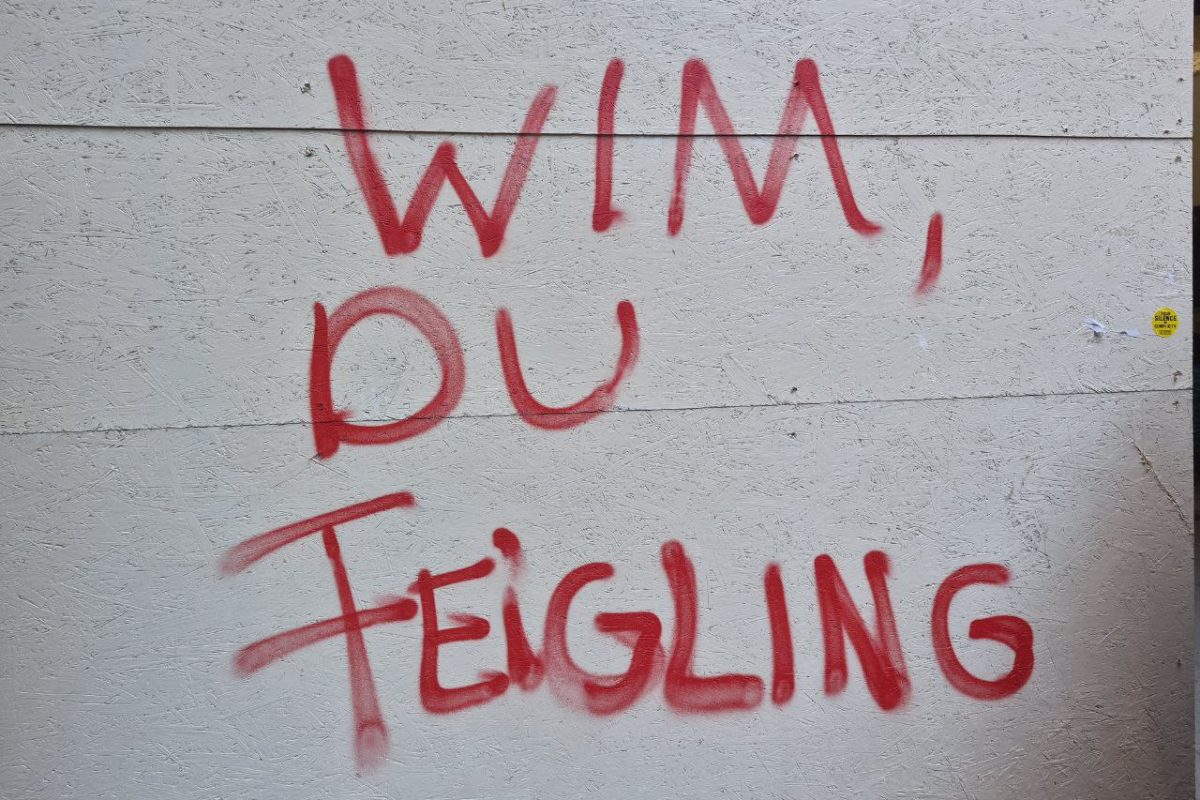

Alternative Jewish voices, such as Jüdische Stimme, face terrible persecution. The Berlin government is trying to shut down Oyoun, a PoC-run cultural center due to claims of “hidden antisemitism.” Oyoun’s “crime” consisted in providing space for Jewish voices who don’t agree with Germany’s Staatsräson. Anti-Zionist Jews have been detained, fired from their jobs, spat on, and assaulted by cops — without a word from the Central Council. As Dische-Becker has calculated, some 30 percent of the cancellations due to supposed “antisemitism” have been directed against Jews.

On December 11, the German government and the Central Council organized a pro-Israel demonstration at Brandenburg Gate. Despite hundreds of organizations signing the call, a grand total of 3,000 people showed up — including numerous Iranian monarchists waving the flag of the Shah. Very few Jewish people chose to show their support for Israel. That same day, just down the road, some 5,000 people had joined one of the almost daily protests in solidarity with Palestine, and many of them used signs to refer to themselves as Jews for Palestine. It is, of course, impossible to know how many Jewish people were at each event. But it certainly seems like far more Jewish Berliners were on the streets for Gaza than were standing with Israel.

This is obviously not to claim that the majority of Jews in Germany are left-wing. But they’re not all conservative either. Here, as everywhere, the Jewish community is endlessly diverse. The Central Council doesn’t represent this heterogenous community — it only represents the Jews that the state wants to hear from.