On 6 October 1960, the film Spartacus opened in New York City’s DeMille Theatre. TIME magazine celebrated “a new kind of Hollywood movie: a super-spectacle with spiritual vitality and moral force”. The New York Times‘ long-time film critic Bosley Crowther was less excited, dismissing the film as “heroic humbug”, adding that “the middle phase is pretentious and tedious, because it is concerned with the dull strife of politics”.

People entering the film had to brave picket lines organised by the right-wing American Legion. The Legion had sent out 17,000 letters, encouraging patriotic war veterans to protest the film. Hedda Hopper a columnist close to the Legion wrote “that story was sold to Universal from a book written by a Commie and the screen script was written by a Commie, so don’t go and see it”.

Said Commie scriptwriter was Dalton Trumbo, whose name appeared on the end credits of a film for the first time in over a decade. Trumbo was one of the “Hollywood Ten”, and had spent 11 months in prison after he refused to testify in front of Joseph McCarthy’s House of Representations Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC). Since 1945, no film had been prepared to publicly acknowledge his contribution, even though he had won 2 Oscars in this period for films he had written using pseudonyms.

For the 12 years following their 1948 trial, none of the Hollywood Ten could openly work in the US film industry. Some got jobs as labourers, some left the country. Others carried on writing – at a much lower rate of pay – under assumed names. By proudly displaying Trumbo’s name, Spartacus was openly challenging the repressive status quo.

But anti-Communist witch hunts weren’t what they used to be. At the Los Angeles première, the 1,500 guests were met by only 36 pickets. By the end of 1960, Spartacus was the year’s highest-grossing film.

Spartacus and the McCarthy Witch Hunt

Spartacus was created in a Hollywood still reeling from McCarthyism. Trumbo’s script reminds us of the indignities that he was still suffering. When the proto-fascist senator Crassus declares “the enemies of the state are known, arrests are in progress, the prisons begin to fill. In every city and province, lists of the disloyal have been compiled”, Trumbo knew that his name could be found on similar lists which had been compiled much more recently.

Although McCarthyism is now generally thought of as a Hollywood phenomenon, its purview was much wider, as was its aim of smashing all radical opinion and social resistance. Norma Barzman, who was forced into exile by the blacklist, explains: “they attacked Hollywood because it was high profile and made it easier to create a climate of fear. The blacklist was a small part of what was going on in this country at the time”.

The 1950s had not started well for the political left. Stefan Bornost reports that “unlike the 1930s which was characterised by large social struggles, workers did not break in large numbers from the system and towards the Communist Party (CP). Instead they were increasingly integrated in the developing conservative and anti-Communist Cold War Consensus. The CP thus lost both political perspectives and members. Party membership fell from 80,000 in 1944 to 5,000 in the mid-1950s. Of these 5,000, around 1,500 were FBI informants”.

In 1952, the US Chamber of Commerce recommended barring “Communists, fellow travellers, and dupes” from jobs as “teachers or librarians,” and from posts in “any school or university.” Specifically targeted were “the entertainment field” and “any plant large enough to have a labor union”.

McCarthy was helped by the Business Union perspective of the big Union Federations, which actively worked to police the attacks on the left. “In 1949, the CIO expelled 11 ‘red’ unions. By 1954, 59 out of 100 unions had changed their constitution to bar communists from holding union office–a provision that was only recently dropped – and 40 unions barred communists from being rank-and-file members”.

Left-liberal acceptance of McCarthyism went beyond the trade unions. “The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), instead of defending communists, conducted its own witch-hunt to oust radicals from its ranks –such as ACLU founding member Elizabeth Gurley Flynn”.

Spartacus was a product of a time that had experienced these massive defeats, but was also slowly starting to recover. By the late 1950s, some of the trade unionists who had been destroyed by McCarthyism were starting to regroup. If you are inspired by the famous “I am Spartacus” scene, just think what this basic show of solidarity would have meant to the socialists and trade unionists who, after years of betrayal by politicians and trade union leaders, were starting to organise again.

,,,,Who was Spartacus?

Spartacus, the film, is based on a novel of the same name written in jail by the Communist Howard Fast. Fast, a one-time recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize, had also been brought before the HUAC and subsequently imprisoned. In his autobiography, he wrote “It would be a safe bet to say that before the appearance of my book and the film that Kirk Douglas made from it ten years later, not one schoolboy in ten thousand had ever heard of Spartacus”.

In his article Who was Spartacus?, Paul D’Amato notes that “there are scarcely 10 pages written about [Spartacus’s rebellion] by ancient historians”. Historian Theresa Urbainczyk wryly notes that “slaves did not write their own history; we only know about them from the élite who won, who wrote the history and stamped their interpretation on events”.

Director and leading man Douglas had a similar analysis: “Spartacus was a real man, but if you look him up in the history books you will find only a short paragraph about him. Rome was ashamed; this man had almost destroyed them. They wanted to bury him”.

Yet Spartacus’s story was not unknown to socialists. In a letter to Engels, Karl Marx called Spartacus “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history”. In an answer to a survey by his daughter Jenny, Marx named Spartacus as his hero. Theresa Urbainczyk notes that Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of slave revolution on Haiti was dubbed the ‘black Spartacus’ by an admirer.

When Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht formed the organisation which was to become the German Communist Party, they called it the Spartacus League. Indeed, Fast’s initial interest in the Spartacus story came from his attempt to rehabilitate Rosa Luxemburg and the Spartacus League as alternative figureheads to the discredited Josef Stalin.

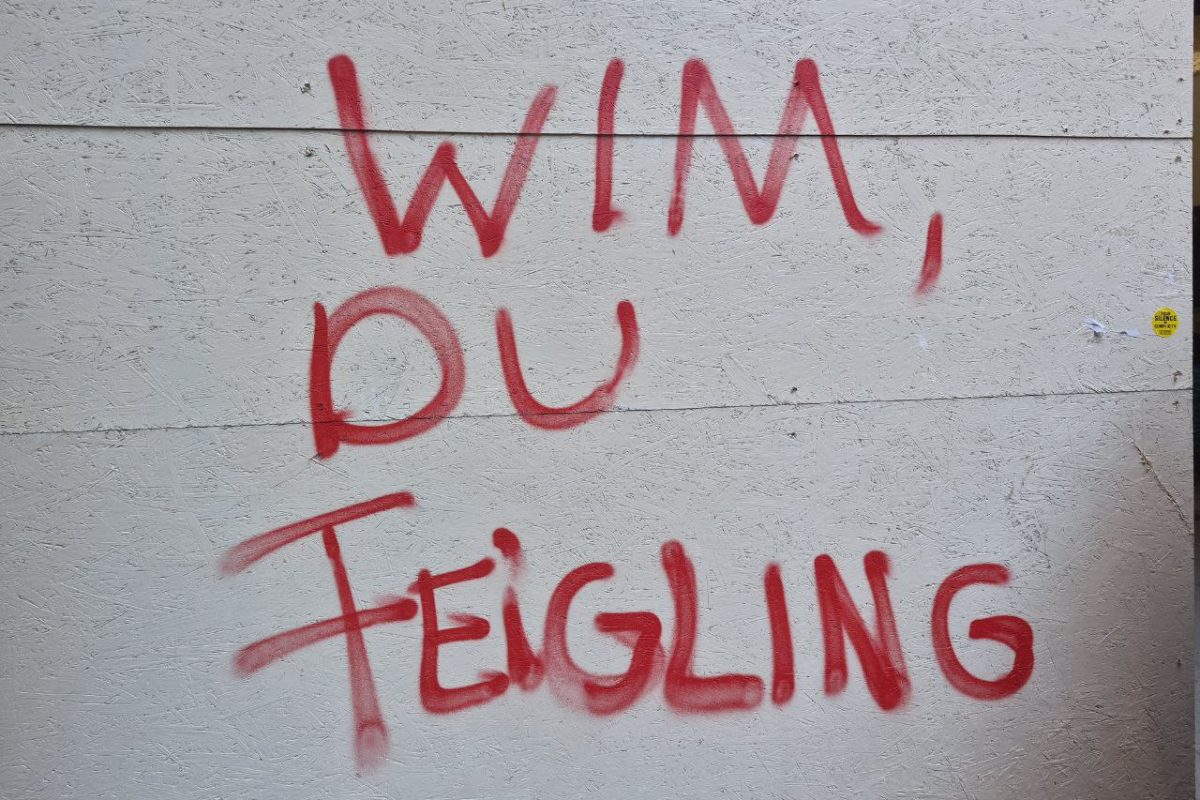

The Introduction to Urbainczyk’s book about the film starts with a quote from Liebknecht, taken from a memorial in Berlin-Mitte [1]: “Spartacus means the fire and spirit, the heart and soul, the will and deed of the revolution of the proletariat”. In a footnote, Urbainczyk continues: “Liebknecht goes on to say ‘Spartacus means every hardship and every desire for happiness, all commitment to struggle of the class conscious proletariat. Spartacus means socialism and world revolution’”.

Spartacus was also praised by Enlightenment liberals like Voltaire. In the Soviet Union, many sports societies were named after Spartacus, the most famous being Spartak Moscow (renamed in 1935). So although Spartacus was not a household name before 1960, he did hold a place in a certain popular consciousness.

For Urbainczyk, “Spartacus is like Che Guevara, of whom many people have heard but about whom far fewer know very much. It is not important for them to know about him because he simply represents the idea of fighting back, or not being crushed”.

This is the opening to a longer article which will be published in the near future

Footnote

1 In DDR times, this Berlin monument was open to the public. It is currently behind locked gates in the back garden of some luxury flats. To view it, you need to wait until a yuppie family goes for a walk and sneak through the gates.