In 1960 Ghana became the first colonised African nation to declare independence. Kwame Nkrumah was Ghana’s first president and a pioneering thinker and intellectual, contributing to the foundations of the theory of Neocolonialism. As more countries won independence (the UN grew from 51 Nation States to 144 between 1945-1974), new governments, such as that in Ghana and in Tanzania under its first president Julius Nyerere in 1964, began to enact their political programs.

Michael Manley arrived as President of Jamaica in the early 1970s. Manley wanted to utilise the numerical advantage the new postcolonial nations had in the UN, and together with Nyerere, Nkrumah and other heads of nations, they proposed the New International Economic Order (NIEO) which was passed by the UN General Assembly in 1974. This, among other things, secured sovereignty over natural resources.

“The first generation of nationalist independence leaders like Nyerere and Nkrumah had already learned a painful lesson regarding the limits of sovereignty. Resource-rich ‘independent’ countries still found the rules of international trade weighted against them.”

-Kojo Karam, Uncommon Wealth

Nkrumah, Nyerere and Manley saw federations as a way to combat and fix the structure of the economies of their and other countries, which had been built during the colonial period to exclusively serve metropoles; export oriented economies, whose main function and corresponding infrastructure existed for the extraction of raw materials. These raw materials were to be exported and processed outside their country of origin, reducing the need for infrastructure. Early attempts (and many later ones) to reshape their economies to serve the peoples of their respective countries were thwarted and systematically put down in many ways, ranging from bureaucratic and legal to outright military sabotage and (re-) invasion. Any hope of the NIEO functioning as planned were struck down by Thatcher and Reagan’s administrations.

The economic order formed during the colonial period was not to be challenged or changed in any way. In response to the solidarity and organising happening between decolonised and decolonising nations, the former colonial powers and global capital (in lockstep) acted in different ways to maintain the status quo ante and keep these economies subservient to those in power in the Global North. Much of this organising happened in the by then 20 year old World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

It was during this first phase of decolonisation (1940s around the war) that the Bretton Woods Institutions (the World Bank and the IMF) were set up. The World Bank was established to give loans to countries who are unable to qualify for commercial loans. The first loan the World bank issued was in 1947 to France to help reconstruct after the destruction of the second world war. In 1948, Chile received the first ‘Development Loan’ to help the country “grow its economy and better integrate” – no prizes for guessing what integration means in this context. Fast forward to 2002, and Chile receives a loan for the third ‘Road Sector Project’, partly to aid the maintenance of the roads financed under the first two projects, but also to “support the government’s privatisation efforts”.

Loans come with conditions and when there is no choice as to whether one accepts the loan or not, conditions become demands.

The rest of the article will focus on one aspect of the enormous legal framework built into the development industry. It is known as the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system. One very destructive tool from the neocolonial toolbox.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement System

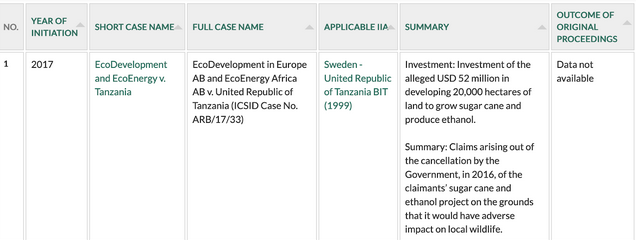

In December 2022, an Air Tanzania plane was seized in the Netherlands. Dutch authorities were acting on behalf of Swedish company EcoDevelopment, to whom the Tanzanian government owes $165 million dollars.

-The Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator entry of the EcoDevelopment vs Tanzania dispute

The company brought a case against Tanzania, suing for losses in profit, after the Tanzanian government revoked a land title for a sugar project on grounds of “concerns over the impact on local communities and a wildlife sanctuary.”

The case was heard at World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and came down in favour of the Swedes, declaring that Tanzania must pay EcoDevelopment for loss of potential profit. Such legal action is made possible through the Swedish-Tanzanian Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT). One day after Tanzania put forward an appeal to annul the decision, the Dutch authorities seized the plane. The plane, incidentally, was released about a month ago.

This sounds absurd upon first reading.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement system is a legal mechanism written into many trade agreements and treaties to settle disputes occurring between nation states and companies. An investor from one signatory state can sue the other state for laws or regulations which may negatively affect its expected profits or investment potential. If the investors win, they will be awarded compensation in a binding arbitration tribunal. Cases are heard in one of two places, either at the United Nations Centre for International Trade Related Arbitration Law or at ICSID at the World Bank.

If the country disagrees with the ruling and refuses to pay, it may have its assets seized internationally. Even before there has been a chance to appeal, as we saw in the case of EcoDevelopment vs Tanzania.

Let us give one more particularly heinous example. In 2007 the two Italian owners of Finstone Ltd, a mining company in South Africa, brought a case against the South African government over the so-called ‘Black Economic Empowerment’ (BEE) policy. The BEE requires or offers strong incentives for South African companies to have 25% of shares in black ownership. BEE was introduced to redress the deep, persistent structural inequalities caused by the Apartheid regime.

“We are saying that these Italian investors are unfairly discriminated against in relation to BEE investors in South Africa,” said lawyer Peter Leon on the behalf of the investors. They sued the South African government for 266 million euros. The South African government settled for an unknown amount.

The BITs under which these suits were offered to the South African Government should be viewed with particular scepticism; South Africa emerging from the Apartheid era having suffered economic isolation and decimation was in desperate need to reintegrate into the global economy and to kick-start its own.

Often, these BITS or Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have so-called sunset clauses written into them. This means that if a given government chooses to revoke one of these agreements – which often contain far more than the ISDS clause – then one must wait 5-10 years before it loses its effect. The idea being that, in this time a more favourable government can come into power and undo the undoing.

An industry has formed around these disputes, and financial institutions will offer loans to companies against winnings to pursue ISDS cases. In cases where a country does not possess a BIT or FTA containing an ISDS clause, one can set up a shell company in a country which does hold such a clause and take legal action from that country.

At the time of writing 37% have resulted in favour of the state, 28% in favour of the investor and 19% settled. The remaining cases were discontinued or thrown out. The full breakdown and other stats can be found here. However, there is no ‘winning’ one of these disputes for a state. The legal proceedings are extremely expensive and legal fees have only been awarded in less than half of cases where the state won.

In Claire Provost’s and Mathew Kennard’s new book ‘Silent Coup’ the full story and history can be found, detailing celebrated German economist Herman Josef Abs (on the board of Deutsche Bank during the NZ and negotiator of the post war settlement with Israel – given this job by Adenauer) and the origins of ISDSs. In short, Abs’ proposed a legal framework in response to several events – such as the Mosaddegh’s nationalisation programme in Iran which saw the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s assets seized in 1951 – as a way to protect former colonialist’s assets and property. In its modern form, ISDSs provide legal protection for assets and ‘potential profit’ loss of international investors.

This is all shrouded in secrecy, and it’s very hard to gain access to documents concerning these cases. That which makes it to the public arena is collected and reported by the ‘ISDS Platform’ and can be found at the “Investor State Dispute Navigator”.

What can be done?

The discussion around ISDSs is increasing and there is a growing movement for abolishment, or at least for reform. In 2019 the UN Conference for Trade and Development (UNCTAD) published a report on reforming the ISDS system. Some of the reforms documented there are promising, but progress is slow:

“The EU is proceeding with plans for establishing a multilateral investment court. Recent EU member States’ bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with third countries include certain procedural improvements, aligned with the EU’s broader investment policy approach. New policy documents have set a timeline for the termination of intra-EU BITs, which will remove access to the ISDS mechanisms contained therein.”

– International Investor Agreement (IIA) Issues Note, UNCTAD 2019

Here in Europe, we must increase the pressure on the EU to push reform further and make it happen faster. In the US however, contradictions are rife. While in the context of the IIA, the US is committed to a “wide spectrum of reforms” to the ISDS agreements in place, the State Department still see the presence of ISDSs as a requirement for economic relations (for example in the “2023 Investment Climate Statement for Zimbabwe”).

Conclusion

These institutions established in the aftermath of the second world war under the auspices of providing vital financial support have become one of the most unchallengeable, Goliath pillars in the international economic neocolonial, neoliberal order. This is what the established development industry is today. It functions to serve corporations. I don’t challenge the hearts of every person working within this system, however, that they can’t or won’t see that the system is causing immeasurable harm and is what empire and colonialism has morphed into today is only possible due to the same white supremacist ideology which existed throughout the colonial period and is a key, if often an invisible, component of the wider neoliberal ideology.

I’m not here to say that the transfer of money from the global north southwards is a terrible thing and should be stopped, exactly the opposite; we need a huge redistribution of wealth extracted and stolen. We need to redress the underdevelopment of Africa by Europe. The ISDS system is a tool actively underdeveloping Africa. We must fight to nullify ISDSs between countries where they are not wanted and to cancel debt incurred.

This is the first of a series of articles by Dominic Bunnett on theleftberlin.com. Future articles will examine how ISDSs play a role in Zimbabwe’s land reform program and debt and how they are crippling efforts to globally fight climate change.