Rebellious Daughters of History #31

by ,,Judy Cox

The First Black Communist: Grace Campbell (1883-1943)

Grace Campbell was born in 1882 in Georgia. Her father was a Jamaican immigrant and teacher and her mother was a woman of mixed African American and Native Ameri- can heritage. The family moved to New York City in 1905 and Grace devoted herself to community projects such as the Empire Friendly Shelter, a home for unwed mothers.

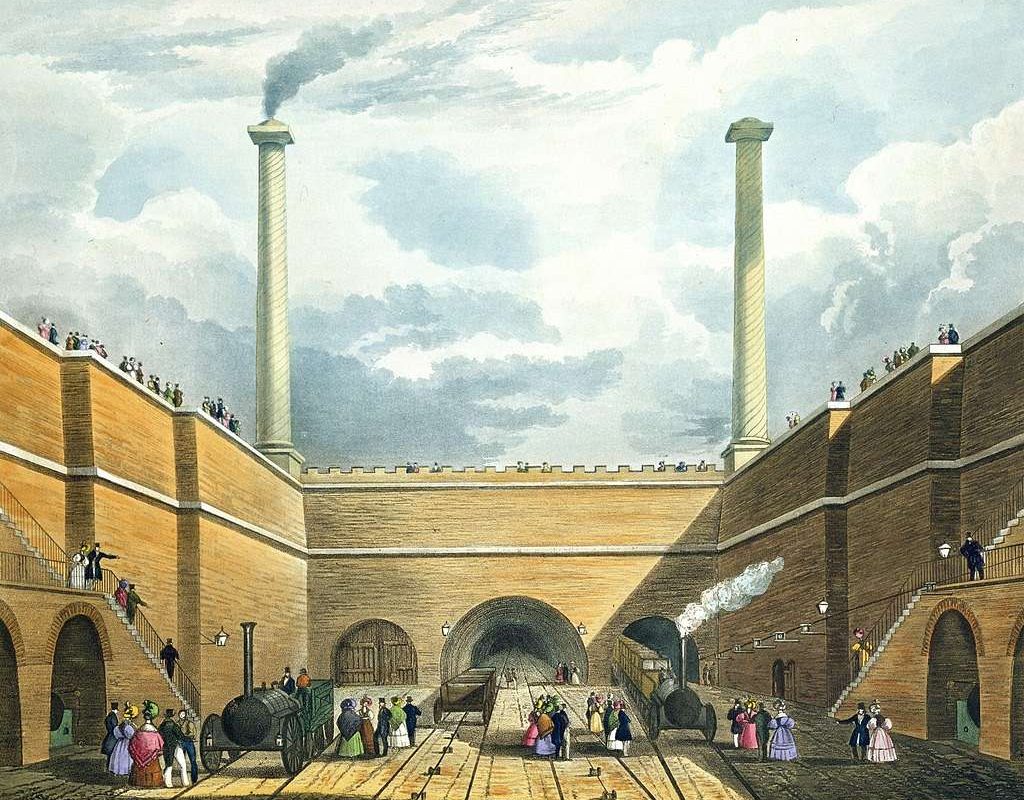

In 1911, she became the first black woman appointed as a parole officer in the Court of General Sessions for the City of New York. She worked as a jail attendant in the women’s section at “the Tombs,” New York’s infamous prison, until her death in 1943.

Grace became active in the Socialist Party of America, the first African American woman to join the party. Her involvement in the Socialist Party in New York placed her in a community of radical women, many of whom were gay and bi- sexual, and agitated for birth control, free love, and gender equality.

In 1920, Grace helped found the People’s Educational Forum in 1920, a forum for debating socialist and black nationalist ideas.

Grace played a pioneering role in Harlem’s early 20th century radicalism and was the most prominent woman in the Harlem Left.

In 1919 and 1920, Grace ran for office in the New York State Assembly on the Socialist ticket. Her groundbreaking ticket won 10% of the vote, nearly 2,000 votes, more than any other black Socialist party candidate. Grace was the first African-American woman to run for public office in the state of New York.

In 1921, she moved away from the Socialist party and was a founding members of the African Blood Brotherhood, which advocated armed self-defense, equal rights, and self-determination and was known as the first Black communist organisation. Grace was the only woman in the leadership of the organisation, which met in her Harlem apartment. Her home remained a busy hub of radical political activity into the 1930s.

In 1923, Grace became the first black woman to join the Communist Workers’ Party and worked as an organizer. She combined community work with a socialist political vision, called for world revolution and focused special concern for black women’s freedom and a passionate commitment to the Communist movement. Later, Grace fell out with the Stalinist leadership of the international communist movement.

Grace was monitored by the FBI, which noted that she carried the Bolshevik red card and reported: ‘Grace Campbell showed herself an ardent Communist . . . Though employed by the City Administration, is frank in her disapproval of it and said the only way to remedy the present situation was to install Bolshevism in place of the present Government.’ (FBI, 4 March 1931)

Grace never married or had children. She continued her work in socialist politics and civil service until her death in 1943, aged 60.

Not just Mrs Lenin: Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939)

Nadezhda (Nadya) Krupskaya was born to a noble but impoverished family. She won a medal at school but was excluded from higher education because she was a woman.

Nadya was already a well-read Marxist when she met Vladimir Lenin in 1894. In October 1896 she was arrested and was allowed to join Lenin in exile in Siberia on condition that they married.

In 1900 Nadya published a pamphlet, The Woman Worker, which explained how women could liberate themselves.

Released from exile in 1901, Krupskaya joined Lenin and spent five years in Munich, Paris and London. Leon Trotsky described how Nadya, ‘received comrades when they arrived, instructed them when they left, established connections, supplied secret addresses, wrote letters, and coded and decoded correspondence. In her room there was always a smell of burned paper from the secret letters she heated over the fire to read’.

After the 1905 Revolution, Nadya returned to St Petersburg and became secretary of the Central Committee before being forced back into exile. She was one of the first Marxists to formulate a socialist theory of education, writing ‘Public Education and Democracy’ (1915).

In the summer of 1917, Nadya became a member of the Vyborg Bolshevik Committee. She was also chair of the Vyborg Committee for Relief of Soldier’s Wives.

In August 1917, Krupskaya was a delegate to the Sixth Party Congress in renamed Petrograd. On 5 October she was one of a seven-person delegation from the Vyborg District to the Bolshevik Central Committee argued in favour of the October Revolution.

Nadya joined a government body devoted to eradicating illiteracy and setting up libraries. She became a prolific author and orator. Her biographer wrote that she, ‘hurled herself at a furious pace into the impossible task of designing and constructing a human, cultivated socialist system of education in a country that was economically ruined, racked by civil war’.

Free and universal access to education was mandated for all children and the number of schools doubled within the first two years of the revolution. Co-education was immediately implemented to combat sex discrimination, and for the first time, schools were created for pupils with disabilities.

Nadya survived for 15 years after Lenin’s death in 1924, both defending Lenin’s legacy and making compromises with Stalin to survive. She dedicated her life to the struggle for a better world and was a revolutionary in her own right.