Your film “Klassenkampf” (Class struggle) shows your development from the child of a working-class family in a Swabian village to a film maker and author in Berlin. For those who haven’t seen the film, can you quickly explain your history?

I grew up in the mid-60s in a Swabian village constricted within the so-called “precariat” – the class of workers, craftsmen and farmers. I was expected to follow a regulated, traditional life. With puberty came politicisation and my first attempt to break out of this milieu. Then civilian service, theatre school, journalism and abandoning my origins, while I was failing to enter the new class or to take root in the new milieu.

You have made a very personal film. How much can we generalise from your experiences? And is that important?

If it were just about me, I wouldn’t have to make a film; that would really be too banal and unimportant. In truth, it’s about more. In this scream, I am a projection screen: my life is an example from which you can generalise. My experiences are also the experiences of many others, of the class politics. But as addressed in Klassenkampf it is based on my life. It explains a social background based on my biography, as an exemplary representative for many. It is significant that the question of class emerges from these lower classes of society.

You quote several progressive academics and authors, such as Didier Eribon and Annie Ernaux. To what extent do their beliefs correspond with your own?

Didier Eribon’s fantastic book “Returning to Reims” was an awakening for me; and opened my eyes to the fact that so-called “class-ism”, the desire for “social mobility” and all that this entails – isn’t an individual phenomenon but is widespread.

You refer to Eribon’s analysis of the precariat. He says that this term is now used more often than working class. Later, he says that the precariat is the new working class. Does the working class still exist in the old sense of the term? What has changed?

I think that Eribon does that well. He extends the term “working class” and adapts it to contemporary social and political conditions. The class of workers no longer consists of people who have work but above all and in larger numbers people who have no work. What unites them is the precarious conditions in which they must live.

I think that some things regarding this really have changed and shifted. The industrial disputes of earlier years are not as pronounced in the old form. Regarding the class struggle as I understand it, this is now more about individual advancement and not so much about collective goals such as reasonable pay, equal rights etc. which may have been more of a focus of earlier industrial struggles.

The precariat which is shown in the film seems to be very passive. They suffer, possibly more than ever. But according to Eribon they have few opportunities of organising themselves. Back to the title: where can we find class struggle from below at the moment?

Well, something is happening, but not enough. I think that Georg Sesslen gets to the heart of it: “the precariat is the sphere of devalued work and disenfranchised people. It is a class which has no party and no organisation, no project and no consciousness. It is the class of the long-term isolated.”

He than asks about possible consequences: “how would it be if, instead of the precariat fighting itself in its segments, condemning and mistrusting, it began to regard itself as a class? How would it be if the precariat were aware of its strength and recognized itself as a political subject?” I think that then there would be something to win.

You, and many who you quote – have halfway gone over from one class to another. In other words, you don’t seem to feel full comfortable, either with the workers and farmers at home, or with the élites in the world of art. How do you understand class? Is it a feeling, a relationship to the means of production? Or a little of both?

Class is the vessel in which all fragments of identity are contained: cultural, religious, political, gendered, sexual, drifting around in different mixes.

The class from which I came, is above all characterized from “classism”, that is discrimination because of social origin; the social position goes along with exclusion, stigmatization, discrimination – in the form of education injustice, bad pay, exploitation which was and is apparent in many aspects.

The desire to leave your class of origin is not just because of this, but also because of forms of discrimination within the precariat. I have sensed and experienced racism, misogyny, homophobia, sexism and antisemitism very strongly in my class of origin.

But “social mobility” doesn’t really function. At least, not with me. Somehow I hang in between, between the stools, or – better said – the classes. Which means that I can’t fully escape the old class of origin, but have also not really arrived in the new class. No surprise really: it takes four generations to really carry our this step.

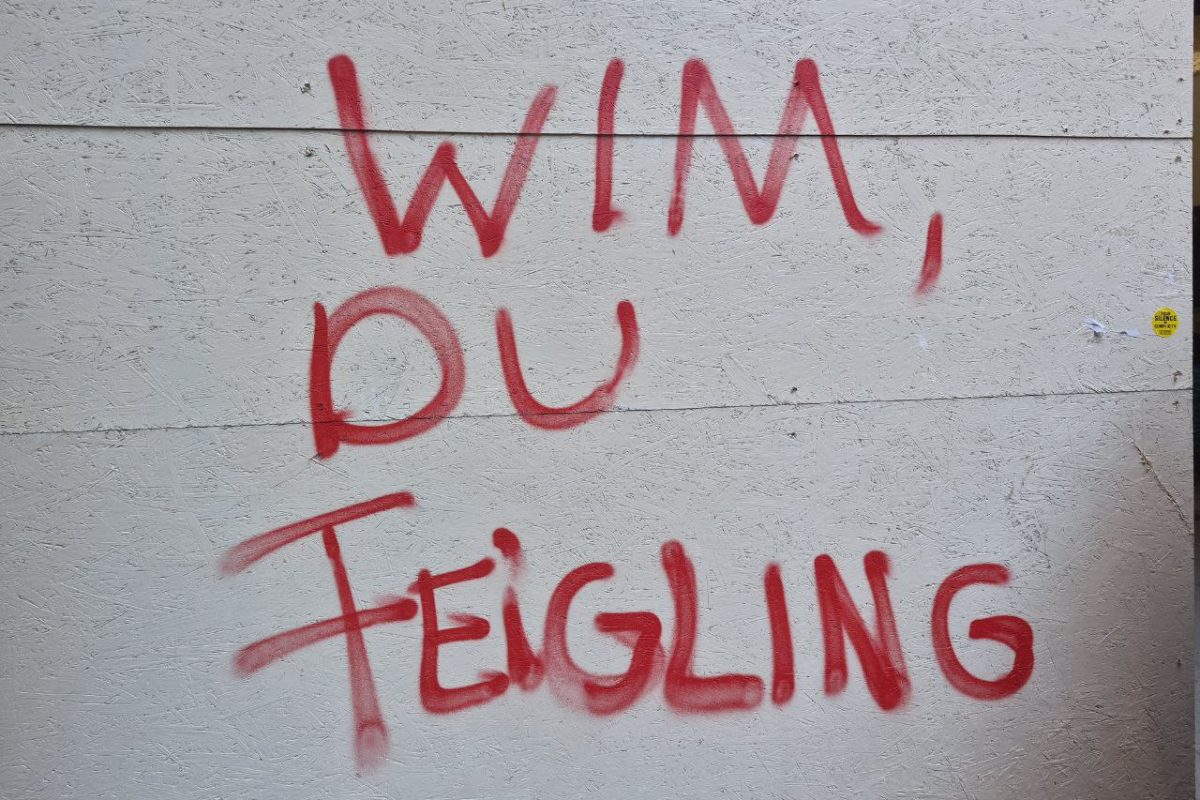

This manifests itself in that I zigzag in my apparent “social mobility”. I feel a traitor to and defector from my class of origin. One who abandons their ideas and principles, and both behind their back and in their eyes betrays them, so that I can take root elsewhere. They really make me feel this whenever I have anything to do with them. They treat me as a deviant, as a refugee, as a crackpot, as one who’s made himself an outcast.

In turn, in the class in which I try to enter, I believe myself to be an imposter, a liar, a fraud, who in principle doesn’t really have the codes, the habitus which this role requires. That despite adopting the signs, the behaviours which are necessary for a lasting imitation. In other words – “how do I deport myself? How do I eat? How do I speak? How cultivated is my conduct? How am I?”

Eribon, and other authors who you introduce are convinced that fights against oppression like feminism and anti-racism must be central part of class struggle. In her new book, Sahra Wagenknecht argues the opposite – that so-called “identity politics” are a diversion from real struggle. What do you think about that?

I’m afraid that Frau Wagenknecht is mistaken, and I find it at times insidious to play class struggle against the fight against oppression. Quite the opposite: you must think of everything together: class politics, classism, racism, sexism, homophobia, misogyny, antisemitism and other forms of discrimination.

Class dynamics cannot be reduced to the dualism between wage labour and capital. Power and methods of oppression like sexism and racism criss-cross class relations and manifest themselves inside them. You must think of a form of collectivity. One which is not aimed at standardizing internal differences, but much more in recognizing them, which ultimately leads to overthrowing class society.

What can sound theoretical becomes immediately clear in practise. The exploited, migrant cleaning worker, or the dark -skinned care assistant do not stand with both feet in the class struggle, but also have one in the debate about racism and e.g. sexism.

You quote Michael Hartmann when he says that the AfD appeals to the poorest part of the population. But according to a study by the Institute of German economy, AfD supporters are paid above average wages. Who is right here?

Well, for sure in a society characterized by racism, the middle class accounts for supporters of the AfD. Nevertheless I believe (and Hartmann verifies it in his study) that that there is definitely a relationship between precarious existences and resentment against strangers.

This is also my experience from my milieu of origin. The separation from what is believed to be foreign was always strong and always there, even when the “foreigners” didn’t directly affect your life. This meant that there was a deeply felt rejection of migrants, although no or few migrants came into our area, The same was so with antisemitism. The AfD is quite consciously and successfully fishing in these murky brown waters.

I agree with most of your arguments, at least in part, and where I have a different opinion, you film has made me think. But one thing didn’t convince me. Shortly before the end, you quote Hermes Phettberg, who says that we must avoid class and retreat to a classless, role-free parallel world of art.

But class isn’t a choice. Most of us work because we must survive. It seems to me that a parallel world of art is a luxury that the majority can’t afford. Or have I misunderstood something?

That is meant to be naturally provocative, also exaggerated, and to a degree meant ironically. The deep-rooted desire to leave these class relationships behind you needs that you deny this class dynamic. This denial, which really seems only available to those who can afford it, also appears to be a privilege, although the real income and living conditions of those who take it is usually close to precarity.

You ask another question shortly before the end of the film: what is to be done? What would be your answer to this question?

Hmm – that is a good, and I think the decisive question. Here I must elaborate a little. The currently dominant criticism of classism – is not aimed at ending class society, but only at a superficial resolution of class antagonism. Those who have become successful are more willingly accepted by those who are longer established and they should then always be friendly to waiting staff and postal workers.

If the latter try hard, they should also be allowed to rise. But this criticism of classism, most definitely does not suggest class struggle, as all demands remain immanent within the system. This is how classism is currently treated socially. I find that this does not go beyond the paradigm of acknowledgement and does not lead to a transition. That can only be achieved by a structural change to the production of misery.

This means: respect doesn’t pay any bills. Or as the Slovenian philosophy rebel Slavoj Zizek says: recognition, respect and attention to workers is only cosmetic for the oppressed class. I also think that the recognition as class probably and ultimately will not lead to a peaceful coexistence of classes. Quite the opposite: it will thus be more accepted as “normal“, as “natural“ and not as something that must be abolished as soon as possible. The fight for economic redistribution is reduced to a cultural question of respectful behaviour.

It would probably be more effective to abolish classes by changing the system. Exploitative neoliberal capitalism, in which very few acquire wealth and prosperity at the cost of the overwhelming majority, must be eliminated.

Capitalism does not just destroy most people worldwide – tramples on their worth and living conditions – but it also rigorously and systematically destroys nature and the environment. It seems to me that the end of capitalism is a precondiition, not just to defeat classism but also to deal with other forms of discrimination.

If the gap between poor and rich is removed; if a just redistribution happens, the common good stands in the foreground; if participation is not just a word but seriously implemented.. equal rights and community spirit are strengthened; sustainability and the defence of nature and the animal kingdom is a decisive factor on which all human actions orientate – Then not only are classes obsolete – But life for EVERYONE will be more worth living.

In this regard we come self-evidently to an overdue dismantling of all discriminations, as well as the fossil resources. Renewable energies are the only ones that we should consider. Basic income is standard, as are equality of education, equal treatment and equal rights. This leads to expropriation of exorbitant private wealth from corporations, and nationalisation of the essential social and political areas – health, education, housing, energy, land, mobility etc.

For many people, this scenario may seem to be a utopia that sounds like a fairy tale, but who is against fairy tales? Dreams are important – they are not lost just because they can’t be realised. They will always be there. At least, the East German Heiner Müller believed this a long time ago. As ever, he is correct.

How and when can we see Klassenkampf? Is there also a possibility for people who don’t speak good German?

The preview premiere was on Friday, 1st October in the Volksbühne Berlin. The cinema release is then in selected German cinemas from 7th October. In some cinemas, the film will be shown with English subtitles. You can find out more on the homepage.

Editor Note: This was edited at points for clarity.