In December 1894, French army officer Captain Alfred Dreyfus was convicted of espionage. The prosecution based their case on a single document—the borderau—which contained apparent proof that Dreyfus had sent military secrets to the German embassy. Even though the borderau was not even written in his handwriting, Dreyfus was Jewish, which was seen by many as proof of his guilt. He was sentenced to imprisonment in a stone hut on Devil’s Island in South America.

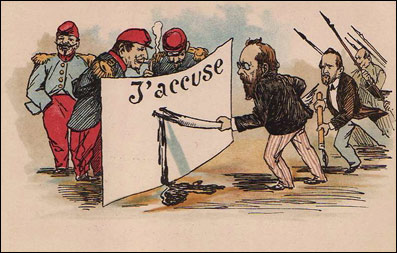

Three years after Dreyfus’s conviction, author Émile Zola took action. Zola was one of the world’s most translated authors—best known to socialists for Germinal, his novel about a miners’ strike. On January 13th 1898, Zola penned a 4,000 word open letter to the French president published in L’Aurore, a Parisian daily paper. It sold 300,000 copies. The article, titled J’Accuse, accused leading politicians and army leaders of antisemitism and obstruction of justice. Zola was not afraid to name the names of the people responsible.

Zola intended to be prosecuted for libel as a result of his letter, so that more facts about Dreyfus’s case would become public. The French establishment reacted quickly, fining Zola 3,000 Francs, sentencing him to a one year imprisonment, and withdrawing his Legion d’Honneur title. Despite this, documents confirming Dreyfus’s innocence remained hidden from the public eye. Zola fled to England until the French president pardoned Dreyfus the following year, albeit with his guilty verdict sustained.

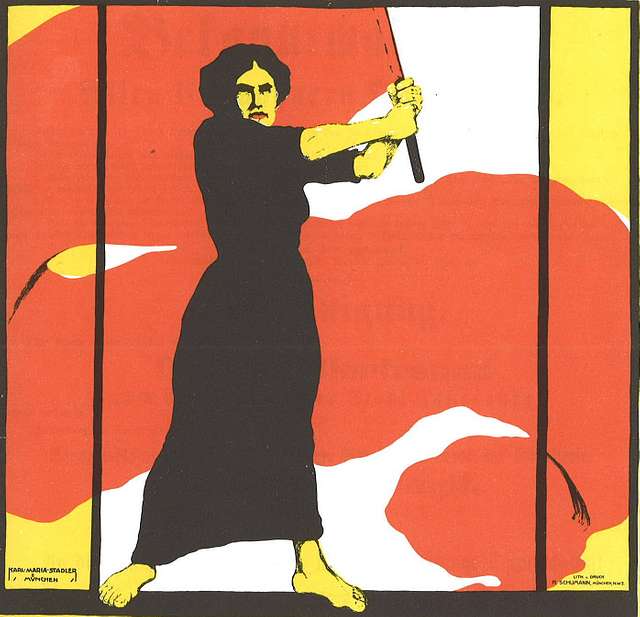

Jules Guesde, a former associate of Karl Marx, argued that the affair was merely a conflict within the ruling class and that the French Left should not support any faction of an army that had recently crushed the Paris Commune—an army in which Dreyfus himself had served as an officer. But French socialist leader Jean Jaurès was a passionate supporter of Dreyfus, as was Rosa Luxemburg, who argued: “The principle of class struggle imposes the active intervention of the proletariat in all the political and social conflicts of any importance that take place inside the bourgeoisie.”

A vast campaign by the League for the Rights of Man organised a mass petition and held public meetings throughout France. In 1906, it finally overturned Dreyfus’s conviction. The Dreyfus Affair has a number of lessons for us today: from the way in which our rulers use racist (in this case antisemitic) attacks to divide us, the need for unity of all victims of capitalism, and the knowledge that while talented individuals like Zola can make important contributions, it is mass action that brings change.