On 26th February, 2026, Sir Keir Starmer’s British Labour Party experienced an electoral debacle. In a by-election in Gorton and Denton, a constituency in Manchester where just 1½ years previously, Labour won 50.8%, they halved their vote, coming third in a constituency which they had held since 1931. Labour was beaten by both the Green Party and the far-right Reform.

The Greens received 40.7% of the vote in the constituency—four times better than their previous by-election result. Party leader Zack Polanski told BBC Breakfast that Gorton and Denton was only his party’s 127th target seat. That is, if they could win here, there were 126 constituencies where they had a higher chance of winning.

Labour were not the only losers. Both the Conservative and Liberal Parties each got less than 2% of the vote and lost their deposits (in British electoral law, if you receive less than 5% of the votes, you have to pay all your own electoral costs). This was only the second time ever that the Conservatives have lost their deposit in a by-election.

This was also only the second by-election where neither establishment party—Labour and the Conservatives—appeared in the top two. The first occasion—when George Galloway won in Rochdale in 2024—only happened because Labour disowned and withdrew their support from their own candidate.

How did we get here?

The Gorton and Denton by-election took place because sitting MP Andrew Gwynne retired on “health grounds”. Gwynne had sent offensive messages in a WhatsApp group, in which he said he hoped that a 72-year old woman who did not support him would die. He was also accused of making racist comments about Black MP Diane Abbott and said that the name of American psychologist, Marshall Rosenberg, “sounds too militaristic and too Jewish.”

Labour had an obvious candidate in Andy Burnham, the current mayor of Manchester who is looking to return to parliament. Burnham is currently very popular, although his politics are at best Soft Left. Starmer and his allies bureaucratically prevented Burnham from standing because they feared that Burnham would try to replace Starmer as party leader. Labour Party rules say that only MPs are allowed to become leader.

Starmer himself was receiving historically low popularity ratings. By January 2026, his unpopularity rating was 75%. Starmer’s net favourability rating of -57 is the joint-lowest recorded for any prime minister other than Liz Truss. Truss was prime minister for just 49 days.

Starmer’s response to his unpopularity has been to tack to the right. In a speech in May 2025, he said that Britain risked “becoming an island of strangers.” These words echoed a notorious speech by racist politician Enoch Powell. Starmer and his advisors were either deliberately stoking racism or woefully ignorant.

As Labour’s campaign stumbled on, they went from crisis to crisis. Less than a week before the by-election, Peter Mandelson—Starmer’s political ally and the man he proposed as US ambassador—was arrested on suspicion of misconduct because of his connections with Jeffrey Epstein. Starmer had already been forced to get rid of both Mandelson and chief of staff Morgan McSweeney.

Starmer’s loyal support for Israel was also damaging his credibility. On 13th February, the high court ruled that the government’s decision to label Palestine Action as a terrorist group (and thus as great a danger as Islamic State) was disproportionate and unlawful. Rather than accepting the court’s ruling, Starmer’s Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood immediately announced that she would be challenging the decision

The Threat of Reform

It is just 19 months since the Conservatives were routed at a general election in which the numbers voting Tory halved from 14 million to 7 million. Both mainstream parties are deeply unpopular. This would be the perfect time for an insurgent left wing campaign. Unfortunately, the main beneficiaries so far of the Centre not holding are Nigel Farage’s right-wing Reform Party.

Reform is funded by shipping magnates, climate change deniers, and investors in fossil fuel. Its website claims: “Net Zero is pushing up bills, damaging British industries like steel, and making us less secure”. The alternative it offers is the oxymoronic “clean nuclear energy.”

Despite recent revelations that Farage conducted “deeply offensive, racist and antisemitic behaviour” at school, including “giving Nazi salutes and goose-stepping”, Reform still tops the polls at 26%, with both Labour and the Conservatives languishing at 18%. Although Gorton and Denton was over 400 on their hit list (that is, there were more than 400 constituencies that they were more likely to win), it looked like Reform had a very good chance of winning.

After the Green’s election victory, Farage raised concerns about “family voting” in Muslim areas—a racist assumption which questions the importance of Muslim votes. We have not heard similar concerns about Christian families who send their children to private schools and all vote for the right.

Matt Goodwin, Reform’s candidate in Gorton and Denton, is a nasty piece of work. He was endorsed by the Fascist “Tommy Robinson.” After racist riots ended with people trying to burn down a hotel containing asylum seekers, Goodwin called this an understandable reaction to “mass immigration”.

Goodwin has also claimed that people born in the UK are not necessarily British, and suggested that women who don’t have children should pay more tax. His campaign manager Adam Mitula was suspended after saying “I wouldn’t touch a Jewish woman”, and denying the Holocaust. But what was he doing as campaign manager in the first place?

The Green Surge

Since Zack Polanski became Green leader less than 6 months ago, party membership has nearly tripled to 175,000. There are now more members of the Green Party than of either the Conservative or Liberal parties.

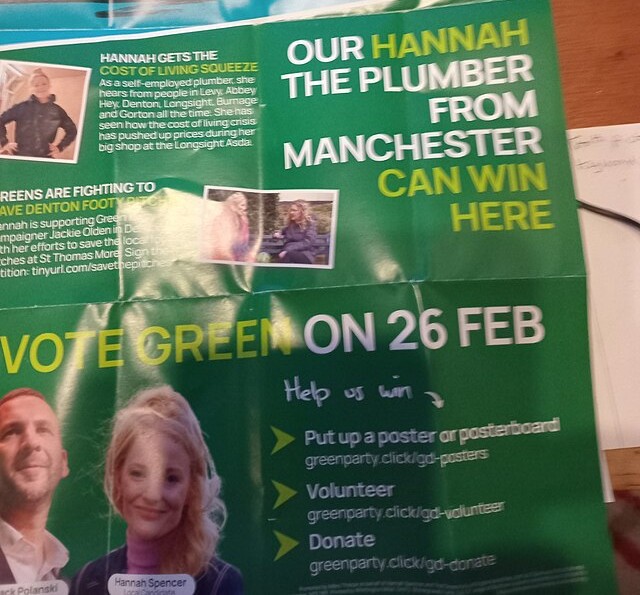

Green candidate Hannah Spencer, a former plumber, wrote before the election: “I’m fighting for lower bills, for neighbourhoods scarred by austerity and underinvestment, and to stop the privatisation of the NHS.” In her victory speech, she added: “I’ve made clear my position and my commitment to working-class communities—the community that I am from.”

The speech also took on her racist opponents, saying “I can’t and won’t accept this victory tonight, without calling out politicians and divisive figures who constantly scapegoat and blame our communities for all the problems in society. My Muslim friends and neighbours are just like me—human.” Spencer spoke at the launch meeting of Women Against the Far Right, and she also released campaign videos in Urdu. She has the potential to provide an important link between parliament and social movements.

Labour’s reactionary response to the Green surge was, sadly, to be expected. Before the election, an anonymous Labour MP said: “The worst outcome for us would be a win for the Greens, or any result which shows us finishing behind them. That could herald the kind of split in the left which we saw in the right at the last election and which gave us a landslide victory.”

Labour’s Negative Campaigning

In the absence of policies which benefitted the local community, Labour’s election campaign focussed on attacking Reform, and—increasingly—the Greens. In the last few days of the campaign, Labour hysterically attacked the Greens’ drugs policy, falsely, and regularly, portraying decriminalisation as being the same as legalisation (it is not).

Policing minister Sarah Jones claimed: “Playgrounds would become ‘crack dens’ if Greens were in power”. Starmer himself said: “the Green Party’s policy isn’t just irresponsible, it’s reprehensible, legalising cocaine, heroin, ketamine and the date rape drug, GHB, a drug which we know is used to spike drinks for women.”

These were not the only Labour lies. On the evening before the election, Labour put out a leaflet saying “Tactical Choice says Vote Labour. Based on a new prediction made in the last 24 hours we are recommending voting Labour.” No organisation called Tactical Choice exists.

Labour’s Facebook page continued this defamation. As it became clear that the Greens were leading in the polls, Labour persistently argued that only they could stop Reform. They posted a series of bar charts of expected results in which the Green prognosis (higher than both Labour and Reform) was absent.

Actions have consequences. There will be future elections in which Labour may well be the party most likely to beat Reform. But voters will remember the lies of Gorton and Denton where Labour’s fear of anything remotely left of centre ended with them trying to sabotage the only campaign likely to beat the Right.

Where was the Left?

While all this was going on, Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana’s Your Party was electing a new executive. This led to rancourous infighting between different slates supporting Corbyn and Sultana. I experienced the worst of this on 61.8% – Supporting Corbyn’s Mandate, another Facebook page which was set up when Corbyn was Labour leader, and often echoed the factional sectarianism found on the Labour page.

On the page, to which only admins could post, there was a worrying number of posts attacking Zarah Sultana and her Grassroots Left slate (sample quotes: “Zarah Sultana does not support or respect Jeremy Corbyn!”, “Revolutionary socialists aka Grassroots left, never miss an opportunity to data harvest”, “Zarah’s disgraceful record!”). In contrast, posts attacking Labour and Reform were largely absent.

Responding to such red-baiting and ad hominem attacks is like wrestling a pig; you both get dirty and only the pig likes it. But one thing needs saying here. One repeated attack against Sultana was that she prematurely announced the founding of a new left party. If Corbyn and allies had not dithered for so many years, it could have been a Your Party candidate who was cleaning up in Gorton and Denton.

Voting for the new executive was supposed to heal these divisions, and yet a couple of days after both elections, a “veteran socialist” and supporter of Corbyn told the Guardian: “Zarah alienated many people in Muslim communities by saying things like there was no place for social conservatives in the party, and we need to rebuild that trust.”

The response from a friend in the UK to this article was “YP is fucked”. The worst way to respond to a radical and insurgent Green electoral victory is by courting social conservatism, or by repeating the slightly racist suggestion that “Muslim communities” are socially conservative. This focus on electoral respectability risks condemning Your Party to electoral and political oblivion.

What next?

Keir Starmer is likely to hang on as Labour leader, if only because there are council elections in May, and the party needs a scapegoat to take the blame for Labour’s almost certain disastrous performance. After that, the party lacks any credible alternative to Starmer. Time will tell whether Labour has damaged itself irreparably, but we should shed no tears at the death of a neoliberal imperialist project.

The immediate beneficiaries of Gorton and Denton are the Greens, long seen as a fringe party. The current Green programme is much more radical than anything offered by Labour. Hannah Spencer’s result is a victory for radical socialist ideas above hate and division. We should all celebrate. And yet, we should remember the experience of the Greens in government.

In Brighton, the Green-led council proposed £4,000 pay cuts, leading to a week-long bin strike. In Germany, where the Greens have come closer to power, they have been much worse, participating in neoliberal governments and providing warmongering foreign ministers like Joschka Fischer and Annalena Baerbock.

Meanwhile, Reform continues to build. It is a sign of how broken British politics are that a nasty, racist party could gain over 10,000 votes in a constituency where 44% of the population identify as coming from a ethnic minority background. That does not mean that there are over 10,000 racists in that part of Manchester, but a lot of people are demanding serious change.

Two days before the election, a man was arrested for carrying an axe into a Manchester mosque. The threat posed by Reform is not just seen in election results, but in giving confidence to violent racists. If the Left is unable to offer credible answers, the Right will exploit the situation.

I hope that Your Party gets its act together and offers a serious challenge to the neoliberal consensus and the far-right danger. Where this means working with the Greens, so be it, but it requires a clear socialist identity, which is not worried about shocking social conservatives. Above all, the Left must combine parliamentary campaigns with a fight on the streets, starting with the demonstration against the far right in London on 28th March.