The results of sunday’s elections are already written. The coalition led by the radical right leader Giorgia Meloni is going to obtain a large majority that may even allow for constitutional changes. The traditional centre-left has completed its transformation into an establishment party and was unable to propose a viable alternative. Conversely, the Five Star Movement completed its left turn and is now competing for the left political space. A reactionary turn in civil rights and an economic policy geared towards the protection of the declining Italian petit bourgeoisie is to be expected in the next years. Most worryingly, an authoritarian turn in the management of conflict and protests is a real danger in the upcoming months.

On the 25th of September, Italy is yet again called to an electoral round, this time with the July fall of the Draghi government. The swiftness gave little space for emerging political parties, especially on the left, to organize. Therefore we will see mostly a change in the balance of power between already established political parties.

Italy experienced one year of technocratic government under the leadership of Mario Draghi, former Italian and European central banker, and one of the main advocates of the regressive economic policies implemented in Italy since the 1990s. This government enjoyed vast support from the media, which started celebrating him even before he could take any real measure. For reasons related to power and ownership, Italian media have traditionally been expression of the will of a narrow circle of powerful business families and have managed to carry a remarkable influence in the way the population has made sense of crisis situations. This time, the media managed to frame Draghi as the almighty “saviour of the Motherland”, a figure that is very typical in Italian politics since the beginning of the 1990s, when the country’s political party system got dismantled. Criticizing Draghi was in itself a matter of stigma, and we may go as far as to say that Italians lived, for one year, in a handbook case of “cult of personality”.

In July, Italians discovered that political support for this semi-god was like the house of straw in the “Three Little Pigs” fairy tale. Conte decided that the Five Star Movement (M5S) would take a more critical stance vis-à-vis the government. Draghi decided to resign, although having the numbers to continue governing without the M5S. Draghi policy making style was extremely authoritative, and every dissent was silenced with a “take it or I leave” attitude. Draghi felt either he would govern with all or with nobody. In the speech before the vote of confidence, he vehemently criticized the right-wing coalition partners, without any apparent reason. Eager to capitalize, the right-wing Lega and Forza Italia parties removed their support to the Draghi government. Thus elections in September.

I will describe the general political situation before the elections and what we may expect in the future.

A black wall: the right-wing coalition.

The general prediction is an inevitable victory of the right-wing coalition. Surveys assess the coalition (Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), Lega and Forza Italia) with 43% to 49% of the vote. With the center-left coalition (in all possible configurations) less than 40% at best. The gap between the two coalitions is maybe as big as 19 percentage points.

These elections signal an impending victory of a coalition led by a right party with roots in the post-Fascist party “Movimento Sociale Italiano” (MSI). Namely Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), with around 22-24% of estimated votes in surveys. Their leader Giorgia Meloni has worked hard to create an image as a “reliable” moderate politician. But FdI is at the radical right, with many overtly neo-fascist members. For migration and civil rights she espouses rhetoric “against the LGBT lobby”, against more generous citizenship admission criteria, and migration. Economically, the party switches between neo-liberal proposals of a flat rate tax and more “social” proposals reflecting the radical right. Meloni’s party is compared to Hungarian Fidesz or Polish PiS. But it is unclear if this is true, since those parties were in government, and sometimes took the “social” vocations of the radical right. For instance, Orbán introduced price caps on some goods and compelled international banks to convert the catastrophic mortgage debt of the private sector into Hungarian Florint (instead of international currencies). PiS also introduced social benefits for the poor that previous governments were not able or not willing to provide. It is difficult to predict whether Fratelli d’Italia will be more inclined to a “social right-wing” or a “neo-liberal right wing” agenda.

There are hints that the next government’s economic policy will mostly skew to the advantage of the petit bourgeoisie, in Italy a numerically substantial electoral group. Why?

First, FdI will be in coalition with the Lega and Forza Italia. Both favour a flat income tax-rate, benefiting mostly the higher-middle class. Such a regressive measure, will hit the public budget harshly.

Second, a July survey highlighted that, the voting intent for FdI is highest among the self-employed and entrepreneurs. The national average of 20.3% of votes, increases to 22.5% and 24.8% among the entrepreneurs and self-employed. The FdI also holds strong among the lowest-income voters, at 21.5%. In general, this cross-class party is skewed towards the petit bourgeoisie. This is relevant, since the Lega, (historically also a party of the petit bourgeoise), saw its consensus among these voters dropping, presumably to the FdI. This suggests FdI is the petit bourgeois party of the coalition, a position consistent a more “social” right.

Lega voter composition is also telling. Its’ national average of 15.3%, the Lega reaches 23.1% among workers in industry, and its consensus decreases with social class, with 19% among voters in the low-income class. This may be partially explained by Lega’s attempt to capitalize on leveraging the anti-migrant sentiment of part of the Italian population. Despite this socio-demographic shift, the Lega still promotes itself as the party of the small-medium sized enterprises, vocally pushing the flat-tax rate. The Lega competes for the base of FdI and Forza Italia.

Overall, the right-wing coalition of Lega, FdI and Forza Italia accounts for 51.2% of the low-income voters in this survey, against a national average of 45.5%. By contrast, the centre-left coalition only accounts for 13.5% of the voters surveyed in this income class.

A centre left for the elites: the PD as the natural continuation of Draghi.

Since its creation in 2008, the centre-left Partito Democratico has always had an ambiguous political agenda. It periodically switches from very mild social democratic stances, to markedly right wing neo-liberal economic policy when in government. The technocratic neo-liberal governments that Italy experienced since the financial crisis found marked support from the PD. The Renzi government was markedly right-wing.

A the current time, the Partito Democratico is clearly positioned at the center or right-of-the-center of the political spectrum. It is similar to the Macron “En Marche” movement: a party of progressive views in civil rights, but highly reactionary in labour and economic policies. Nonetheless, the party tries to make ritual electoral cosmetic adjustments to persuade some left-leaning voters. The official programme and recent statements by politicians, sometimes raise topics like minimum wage, labour de-precarization and taxes on extra profits. Despite the mild to overt hostility that PD politicians have always had towards these topics. This party had promoted the flexibilization of the labour market as a way to “modernize” it, and it promoted stagnation or decline of healthcare expenditure during the Monti and Renzi governments. Hence paper political programmes rarely interpret the political stance of the party. Even the programme of the centre-right coalition includes more inclusive social security, higher minimum retirement benefits, environmental protection and funding for public housing. If even they can pay lip service to social welfare, there is no reason the PD should not be doing so.

The real political paradigm of the PD was overtly for the “Draghi agenda”, and it tries to appear as the natural continuation of that government. This was confirmed by the alliances made immediately after the government fall. These were with the “Azione” and “+ Europa” parties, both economically centre-right and ordo-liberal. The initial agreement anticipated this would give them 30% of contended seats of the coalition, despite their joint political weight being estimated at 5-6% only. By contrast, the alliance with the social democrats of Sinistra Italiana and the Greens, with a comparable but slightly inferior political weight, only gave them 20% of contended seats. Ironically, the alliance with “Azione” was broken only by the will of the “Azione” leader. He suddenly decided that he did not want to ally with the social democrats and greens. Conversely, “+ Europa” remained as the ordo-liberal partner of the PD. To remove doubts, the PD also included in its lists the popular neo-liberal economist Carlo Cottarelli, IMF official and strenuous supporter of budget balance and pension reform.

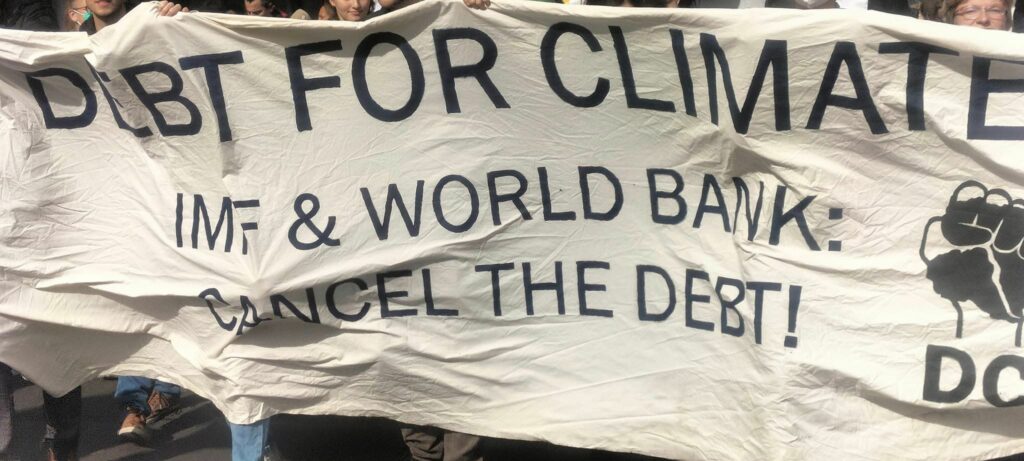

The coalition with the ordo-liberals is fully consistent with the economic paradigm of the PD. It follows the “external constraint” imposed by the European institutions as a religious dogma. Keynesianism and deficit spending in times of crisis are taboos, what matters is that Italy does “its homework” silently and sticks to European guidelines. This neo-liberal dogma has basically destroyed democratic policy making in Italy in the last decade and has contributed to the stagnation. Italian ordo-liberals see European integration as a guarantee that national politics will be deprived of capacity to shape the economy, in favour of a supra-national market-enforcing and budget-disciplining leviathan. This paradigm is fully consistent with Hayek, but also with Italian neo-liberals such as Carli or Maione. The PD leader Enrico Letta is an integral part of this establishment, and was formerly in the Christian Democratic Party (DC) and subsequently on the centrist faction in the PD.

Even on migration, supposedly a civil-right issue, some members of the Partito Democratico often competed with the radical right. They advertised the “success” of an agreement of their former Minister of Interior Minniti, to reduce the number of migrant departures from Libya. But at the price of detaining thousands of migrants in horrific quasi-concentration camps run by Libyan authorities. It is not uncommon to hear PD politicians arguing that they “did better than Salvini” in this field.

The PD electoral campaign is mostly a campaign “in defence of the constitution” and “against the right”. But this defence does not include the most progressive parts of the constitution. Rather, it is interested to avoid a shift to a presidential system, and to ensure that Italian law remains constitutionally subordinated to European law.

The social composition of PD’s voters shows a consistent picture. Data from the previously mentioned survey (IPSOS, 2022), shows that the electoral base of the PD largely overlaps sectors with ordo-liberal thinking. First, among the high-income voters, the PD holds for 31.4% against 20.9% of national average. The preferences for the PD shrinks together with the income class, obtaining only 10% of the voting preferences among the low-income voters (against 21.5% of the right-wing FdI). Other core-constituencies are entrepreneurs and self-employed (24.2%), teachers and white-collar workers (25.4%) and pensioners (29.2%). Conversely, only around 13% of factory workers and the unemployed expressed a preference for the PD. This largely confirms a previous data from the post-2013 election surveys (ITANES, 2013). Namely it is a party that gradually loses voters from the most disadvantaged social strata in favour of the wealthier ones.

The left turn of the Five Star Movement.

After the end of the second Conte government, Giuseppe Conte, former Italian Prime Minister, decided to continue as the political leader of the Five Star Movement, replacing Luigi di Maio. The Five Star Movement’s leadership was now divided between Di Maio, for the moderate “pro-government” area of the Movement, and Conte, for the critics of the new Draghi government. This did not prevent Conte from giving Draghi a blank cheque for the whole first year of mandate, even in regards to the Russian-Ukrainian war. The Five Star Movement was fundamentally a disciplined device to support the government and “rebel” parliamentarians who refused to vote for the Draghi government, like Pino Cabras, were expelled.

This changed in June this year, when Conte decided that the Movement should have been more critical vis-à-vis the government, especially on social policy and on weapons to Ukraine. This escalated tensions within the Five Star Movement between pro-government and anti-government factions. It led eventually to Luigi Di Maio and his circle leaving the Five Star Movement to set up “Impegno Civico”, which placed itself as a “puppet list” of the Partito Democratico.

This final showdown enabled the Five Star Movement to quit the game and refusing to be part of the Draghi government. Nonetheless, Conte initially offered his “external support” to single measures, rather than the whole set of policies. However, Draghi was not eager to accept this and the government fell.

The reasons leading Conte to quit the government are still unclear. The main motivation given was the neglect of the Five Star Movement’s proposals for redistributive policies and social aid in the government coalition. A more critical, realistic view – argues that this was an electoral strategy. With likely social unrest this autumn due to gas shortages and inflation, The Five Star Movement did not want to lose its narrow political consensus by backing a government that, would become unpopular. As Conte put it: “at the election day, it is not journalists or tv commentators the only ones who vote”.

Most likely, both reasons hold truth. The Five Star Movement has steadily declined, dropping from 32% of voters’ preferences in 2018 to 10% this year. Political survival demanded cutting its subordination to the Partito Democratico and launching a “social agenda” occupying the left political space. This is framed as the Five of the Five Star Movement coming “closer to its roots” to capitalize on the social welfare and labour legislative achievements of the first two Conte governments. The genuineness of this left turn is questionable, since previously Conte himself did not seem concerned when the government watered down his “achievements”.

The social background of Five Star Movement’s voters reflects this “social” orientation. The Movement is over-represented among the unemployed, students, and the young age groups, although the loss of consensus compared to 2018 is still remarkable even in these groups.

Conte placed the Five Star Movement as the main left alternative to the coalition led by the Democratic Party and, so far, the strategy seems pay off. The last surveys place the Five Star Movement between 13 and 15% of preferences, a considerable gain from the 10-12% of reported voters’ preferences in July. This places the Five Star Movement as the only “left” alternative among the big competitors in the electoral arena.

The left and Unione Popolare

The big absence is the Italian left, showing little sign of recovery from its two decades-long decline.

Leading up to the 2018 elections, Rifondazione Comunista (Communist Refoundation Party), together with other movements, contributed to the movement “Potere al Popolo”. The electoral result was poor, at 1.13% of total votes. The defeat and internal conflicts led to Rifondazione Comunista quitting Potere al Popolo.

At the beginning of 2022, the wide consensus enjoyed by Draghi seemed consistent with 2023 elections. The fragmented left was thus caught by surprise when, the government fell and elections called for September. A rush to create a project began centring on some keywords.

After the ground-breaking result of NUPES (Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale) in France, Rifondazione Comunista, Potere al Popolo and other minor organizations did “march united” to an “Italian NUPES” – “Unione Popolare”. “Their” Mélenchon was the former Napoli Mayor De Magistris, popular for his victory in metropolitan Naples leading a coalition opposed to centre-left and centre-right.

However, De Magistris is far from Mélenchon. Both with respect to political experience and to his radicality. The UP leader surely can communicate with the spirit of times (i.e. in a populist manner), but he is highly ambiguous on the contents of his proposals.

Above all, on European treaties limiting deficit spending he is ambiguous at best. The programme reads that UP wants to “re-discuss” the Maastricht Treaty and the deficit parameters. However, nothing has been written regarding their intentions if this noble attempt is blocked by Europe, as previously. All governments have tried to re-discuss flexibility with Europe, with little success. We risk the trap, reminiscent of Greece, of a left that promises changes at the European level that will almost surely be denied. In that case, telling electors that you can obtain what you want by applying the treaties as they are is simple electoral fraud, and is not credible. By trying not to hurt the Italian mainstream on the European treaties, they want to challenge the mainstream on deficit spending, without realizing that the two are indissolubly connected.

Beyond this, the UP has an ineffective communication strategy. The “on paper” programme of Unione Popolare is highly ambitious and clearly left in orientation, including the extension of social security to the most vulnerable strata, taxation of the wealthiest, and even nationalizations of strategic sectors. However, people reading programmes on the webpages of parties are a very narrow minority.

In the general debate, Unione Popolare fails to distinguish itself with its’ proposals. In the economic sphere, the keywords were a cap on electricity and gas prices and introduction of a statutory minimum wage. However, both these proposals were also adopted by the Five Star Movement, and the centre-left coalition. Acknowledging this, the only argument for UP is that “the others are less credible”, but this is a poor strategy. Perhaps the most distinctive position of Unione Popolare, was favouring a more independent Italian stance on the war in Ukraine and pushing for a “diplomatic solution”. However, these arguments have not resonated in the Italian public. That is understandably more concerned with the gas bills, rather than with the international situation per se.

Overall, the average voter would struggle to vote Unione Popolare instead of the Five Star Movement, especially when the Five Star Movement is increasingly seen as the most credible opponent to the Democratic Party. The real challenge facing the left now is to take the little it may build in this pre-electoral period and develop it further at the grassroots after elections. Realistically, a mass left movement is not expected probably in the next ten years. The left should thus primarily get rid of its “electoralist bias” leading to these periodical rushes into “unitarian” projects that end up spending the energies of activists for a miserable 1% at the polls.

As capitalist analysts might say, the left must behave like a “long-term investor”; focusing on building ties at local level and achieving recognition by being present in the struggles of Italian workers, and synthesise their needs in a single nation-wide programme. Thereby working “at a loss” for a period, to keep motivation high for a later pay out

Conclusion: What comes next, what to expect.

The electoral game is clear. The right-wing coalition will win, with a strong post-Fascist Fratelli d’Italia Party. What comes next is difficult to forecast, since the situation is unprecedented. But cautious guesses are possible.

Italy’s international position with respect to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Despite the Democratic Party tries to equate the right-wing coalition and Putin, this is barely credible. Although Berlusconi and Salvini have historical ties to Putin and the United Russia party, they stuck to the Atlantic alliance once the war started, although Salvini was more cautious. It is highly unlikely that the right-wing government will be endangered by the war per-se.

The main conflicts are likely to rise in the economic field.

The self-employed workers cannot be ignored. These make up between 21 and 23% of the overall workforce and are right-leaning, and the main target of the right-wing coalition. The whole electoral competition between right-wing parties rotates on fiscal policy, on the flat tax rate. Originally an idea of the Lega, which took it from Orbán, Putin and Trump. It proved popular among the self-employed, hence the other two coalition parties, Fratelli d’Italia and Forza Italia, rushed to adopt a flat rate tax “of their own”. As a result, reducing taxes for the self-employed is a common electoral goal.

However, this flat taxation rate is more to the inclination of Fratelli d’Italia, which may require deploying financial resources, while the flat-tax would cost itself billions of euros. Especially considering that the coalition wants to extend support to families hit by catastrophic energy costs, some compromise is to be done. It is highly likely that Salvini will use his strategy of not taking any responsibility and try to shift the blame of unfulfilled promises on Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia. Similarly, Meloni will try to take a more assertive stance vis-à-vis Brussels on deficit rules, which may contrast with Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, – the “moderate” side of the coalition.

We can expect the next government to be stable as an effect of the large parliamentary support and, economically, to focus on the protection of the declining Italian petit bourgeoisie by subsidization.

On civil rights, the regressive stance of the government is clear to the public. It is however unclear which civil rights will be hit. The most likely scenario is a government blocking any new advance in civil rights, without fundamentally changing anything. It is very unlikely they will enforce a reactionary turn, since this is unlikely to pay electorally.

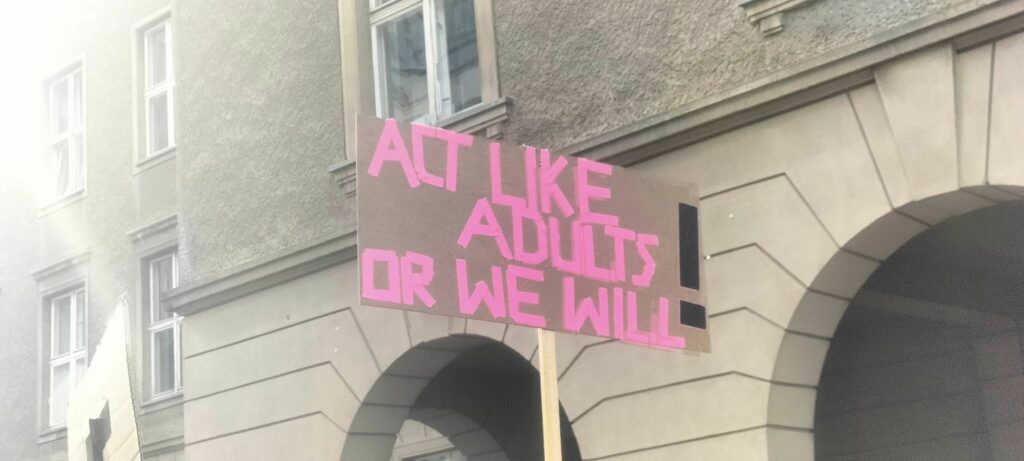

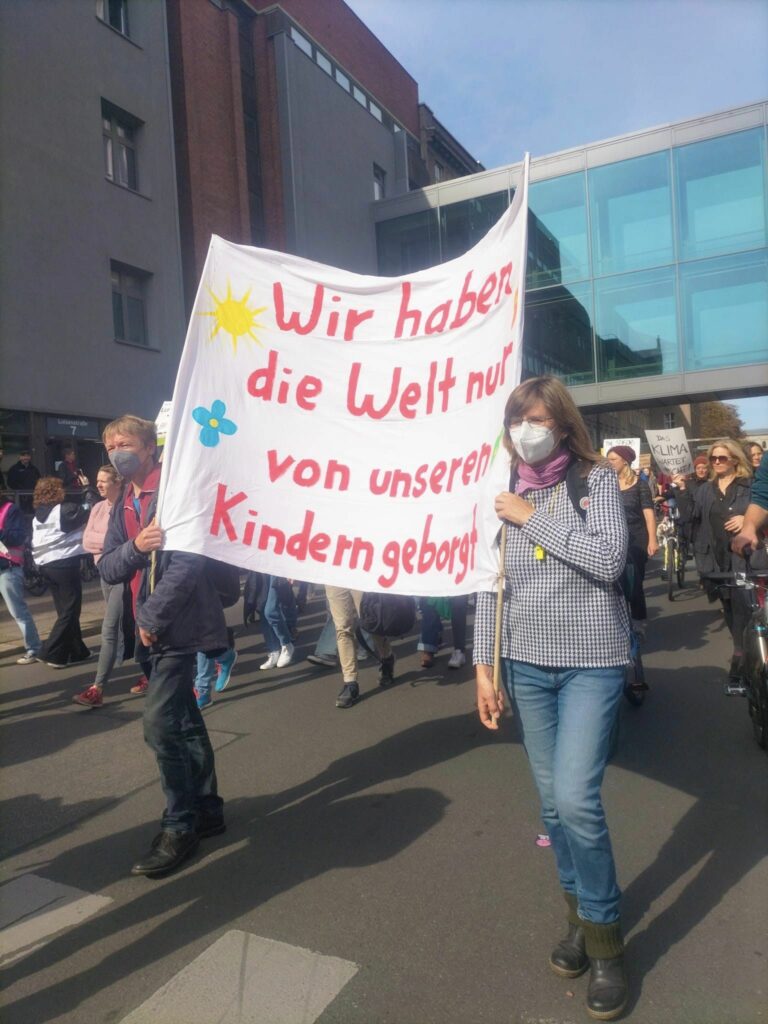

The danger is the authoritarian turn in managing dissenting voices and protests. When Salvini was Minister of the Interior in 2018, the perspectives already were bleak tending towards authoritarianism. The situation is not going to be any better from October onwards. Protests risk being harshly crushed, especially with the upcoming winter and huge social upheavals due to the energy crisis.

Italian unions usually remain silent under centre-left governments, so we may expect them to be more active in organizing mobilization under the right-wing. Equally, we may expect anti-union activity by government to increase, to weaken the bargaining power of unions, consistently with an idea of economic growth based on “internal devaluation”.

A left that wants to be effective in addressing its own social base has thus to start building credibility among people. In Italy no redistributive mechanisms are yet announced to avoid poor households ending up paying 900 euros or more for 2 months of electricity. Equally, taxation on extra profits of the national electricity companies are only on paper. Only 1 of the 11 billion Euros expected was collected by the State. These are the pressing issues the left is called to act upon, to develop a left movement in the upcoming years.