This week marked another important milestone in the ongoing case of Farah Maraqa against international German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (DW). Fatah is one of 7 Arab journalists fired by DW based on allegations of antisemitism. Unlike the climate of the previous trial in July, the room was noticeably empty. In Germany, it is not typical for the parties to be physically present for the announcement of the verdict. However, Farah refused to sit at home and passively await news about the case that has consumed her life for months.

When the court adjourned on 20 July, the judge declared his expectation that a joint statement be submitted by Farah and DW before September 2nd. This joint statement was supposed to set the record straight by addressing DW’s accusations of antisemitism head on. Unfortunately, no such statement was produced due to DW’s clear lack of interest in reaching any sort of joint statement.

According to Farah’s lawyer, Dr. Hauke Rinsdorf, DW’s lawyer denied ever having agreed to the joint statement. In recent weeks, Farah’s lawyer submitted a draft of the joint statement, initiating the court sponsored actions in order to begin repairing the reputational damage caused by DW. But DW produced nothing but silence.

Alice Garcia, who serves as the Advocacy and Communications Officer at European Legal Support Center offered a statement: “The absence of response from DW to Farah’s proposed joint statement as a settlement is indicative of their unwillingness to cooperate and to recognize their mistakes, even after being sued. DW’s new Code of Conduct – which urges support for Israel, among other things – is another indication of this direction: they have not questioned their practices or positions.”

Recent summer months have provided several moments of celebration for a group of 7 Arab journalists fired by DW in February based on specious claims of antisemitism. As of this week, two of the journalists, Farah Maraqa and Maram Salem, have secured strong victories related to the politically charged purge. A third case has been settled out of court, while the others are still pending.

Code of Conduct

Amidst their defeats in court, DW recently managed to find time to concoct a conspicuous McCarthyite addition to their compulsory Code of Conduct, to be signed by their 4,000+ employees of more than 140 nationalities. DW’s new and improved Code of Conduct further reveals their undeniable institutional allegiance for the state of Israel, a foreign government widely considered to be practicing apartheid and systematic human rights abuses.

Ali Abunimah writing in The Electronic Intifada expands on this deeply concerning development: “Despite its court defeats, there is little sign that Deutsche Welle is backing down from its institutionalized anti-Palestinian policies.” He continues, “One cannot support ‘freedom, democracy and human rights’ on the one hand, while also supporting Israel’s racist state ideology Zionism on the other.”

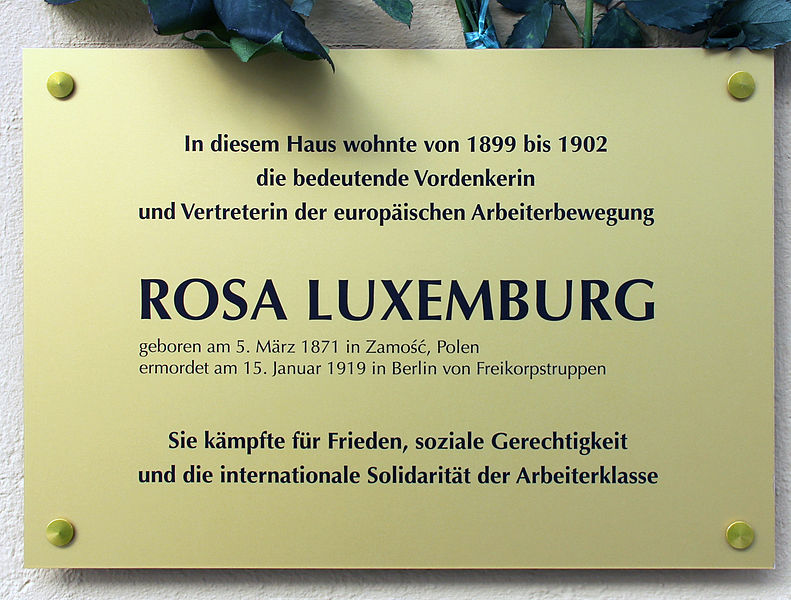

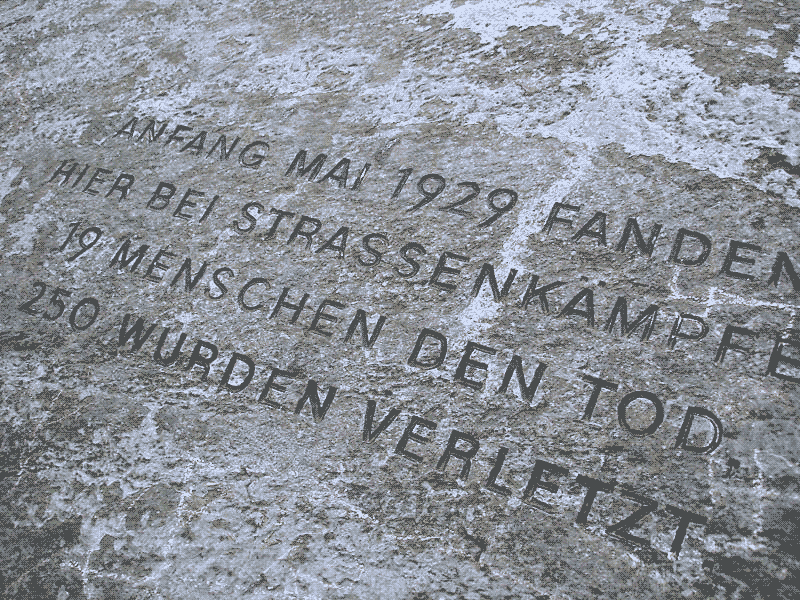

As Hebh Jamal outlines in the +972 Magazine, “In many ways, the broadcaster is simply following the example set by the German government. The clampdown on criticism of Israel in Germany has intensified considerably since the Bundestag adopted the controversial definition of antisemitism, which conflates criticism of Israel with antisemitism, which was put forth by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) in 2017.”

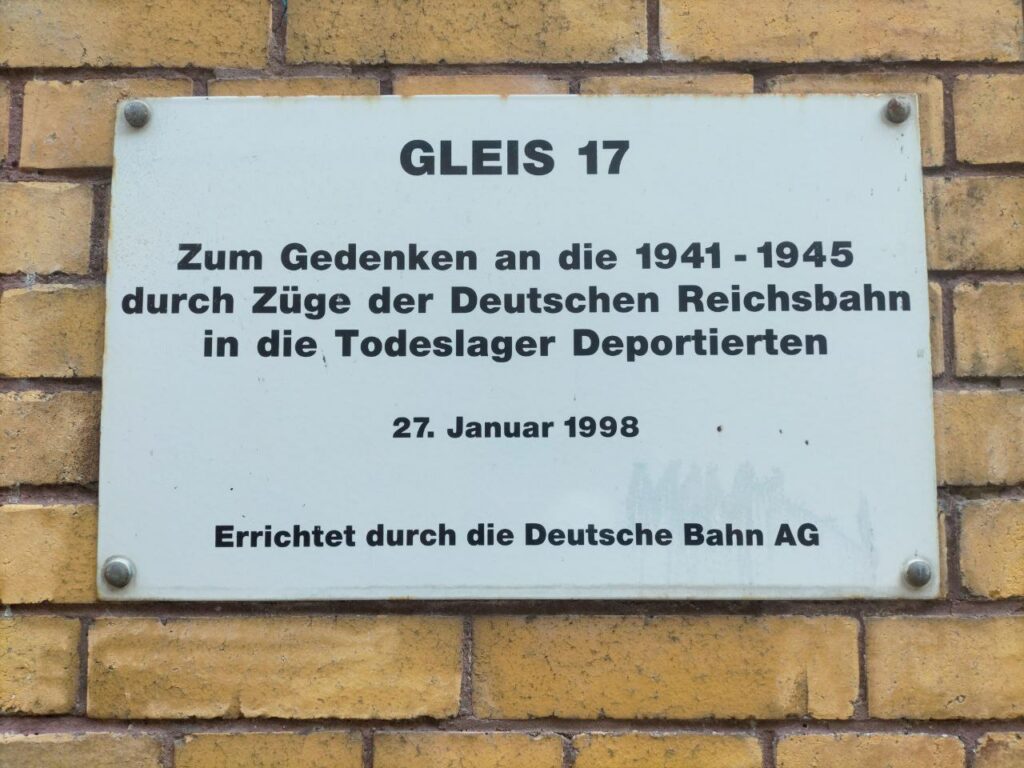

The updated Code of Conduct declares: “Freedom, democracy and human rights are cornerstones of our journalistic and development message and profile. … We advocate the values of freedom and, wherever we are, take independent and clear positions, especially against any and all kinds of discrimination including sexism, racism and antisemitism.” While pretending to prioritize antiracism, the document also states: “Due to Germany’s history, we have a special obligation towards Israel. … Germany’s historical responsibility for the Holocaust is also a reason for which we support the right of Israel to exist.”

A freelancer working for DW offered an anonymous statement to The Left Berlin regarding DW’s recent updates to the employee Code of Conduct: “I felt immediately that it was an invasion of privacy. As journalists, we are of course supposed to maintain ‘neutrality’ and ‘objectivity’ as far as possible, so I do – to some extent – understand not being very overtly political. Not that I think it actually compromises the work, but it opens you up to critique about being biased. But the way that the Code of Conduct was worded was explicitly to say that we are representatives of DW in our private lives, which is very inappropriate from what I see, especially as the whole reason for the Code of Conduct change (Farah’s trial) is completely obstructed. I find the terms of the new Code of Conduct an invasion of my ability to live a private life away from DW, to be honest.” This document further institutionalizes and makes obligatory support for Israel, not only in a professional setting, but in the privately held views of employees as well.

Vindication

On Monday, Farah attended her hearing, accompanied by activist companion Phil Butland. Present in the small courtroom were also the assumed representatives: the judge, a legal intern, and a legal notetaker. Notably absent was any representation from DW’s side.

As the judge announced the verdict, he explained that the legal rationale would be released in 6 weeks time. According to Farah, the judge’s verdict was articulated with great respect and sincerity, and she appreciated his efforts to reiterate and elaborate so that she clearly understood the meaning of his decision.

Phil Butland described the event as a “complete victory.” “The judge was sympathetic to Farah and even quoted her lawyer in the summing up. Although he could only rule on the single thing Farah had said when she worked for DW, it seemed clear that he knew that she is not an antisemite and that Deutsche Welle had no reason to sack her.” The judge even went so far as to explicitly ask if she “understood that she had won,” behavior that is against typical protocol in cases like this.

The judge declared that Farah had won the case against Deutsche Welle based upon several worthy positions that were deemed unlawful in accordance with Germany’s labor law. Firstly, DW failed to adhere to the legal termination terms. Due to the politically heightened nature of this specific termination, it took DW two full months to terminate Farah instead of two weeks mandated by law.

Secondly, regarding the highly contested, allegedly antisemitic writings–the court threw out anything published prior to Farah’s employment at DW, as these were not seen as relevant in the context of her tenure as an employee of DW. What remained was a single statement which Farah has made when she was a freelancer for DW. In this statement she said: “the Israeli experts are putting poison into the history.” The court determined this comment did not constitute justification for the harsh termination Farah experienced.

The court’s stance on the case of Farah Maraqa vs. Deutsche Welle enabled an immediate reinstatement of Farah’s employment at DW, Farah is once again eligible to receive her salary and benefits from DW. The immediate reinstatement of her employment also means that she would be expected to perform her duties at the drop of a hat, should the request be made.

The court ruled that DW must pay all legal fees, which come to over €37,000. Onerous legal fees, like these, typically discourage employees from seeking justice against large institutions like the state-funded media organization Deutsche Welle that can afford drawn out legal proceedings.

A full explanation of the ruling must occur within 3 weeks. After this, DW has 6 weeks to appeal this ruling, which would exempt them from the legal fees. If they win the appeal. But this would require the higher court to overturn a decision that has found Farah innocent on every single count.

What now?

What remains unclear is if DW will choose to appeal this verdict. Farah and her lawyer eagerly await the anticipated release of a lengthy document by the court, due within 3 weeks. This will contain an exhaustive review of the case at hand which outlines the court’s legal position and interpretation of the law in Farah’s case. Based on the release of this information and depending on the specific legal reasoning behind the court’s decision, further opportunities for appeals or other legal actions may present themselves to either Farah and/or DW.

At the time of writing, it remains unclear whether or not the labor court will allow Farah any means of reputational rehabilitation in the form of requiring DW to make a statement disavowing its previous characterizations of Farah as antisemitic. Despite the verdict being cause for celebration, Farah and those who support her still wish to see DW publicly come clean about its slanderous accusations and set the record straight.